If you only have a matter of seconds to look at this review, then here is a visual representation of my reading experience:

Yes, people it was that good, I used gifs!

However, for those who are interested in a slightly longer review, keep reading…

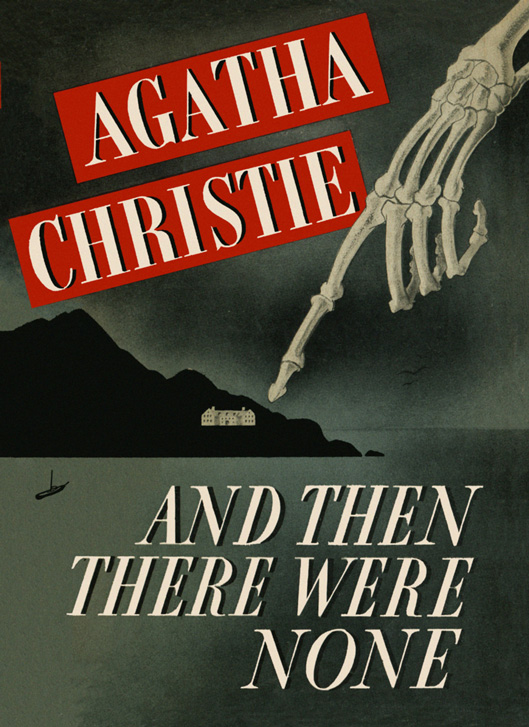

‘Was it the inspiration for Agatha Christie’s And Then There Were None?’ That is the question the Dean Street Press tease readers with on the cover of this forthcoming title. Nine years before Christie’s classic we have today’s read which revolves around an unknown killer as host to a group of invited guests who are picked off one by one, unable to escape.

This book was adapted for both the stage and film, although in the case of the latter it was released under the alternative name of The Ninth Guest. It was the creation of married writing team, Gwen Bristow and Bruce Manning and they would go on to pen three more titles together: The Gutenberg Murders (1931), The Mardi Gras Murders (1932) and Two and Two Make Twenty-Two (1932).

Curtis Evans’ introduction mentions that their first home as married couple, an apartment on 627 Ursuline Street, ‘served as the inspiration for their first mystery novel.’ Evans explains this further writing that: ‘A neighbour tormented them late into the night by loudly playing his radio, in defiance of their complaints, so the Bristow couple consoled themselves by devising their irksome neighbour’s perfect murder. These thoughts of entertaining murder led them to start writing a mystery novel, to which task they devoted two hours every night, plus six hours on Sunday…’

Synopsis

‘“Do not doubt me, my friends; you shall all be dead before morning.”

New Orleans, 1930. Eight guests are invited to a party at a luxurious penthouse apartment, yet on arrival it turns out that no one knows who their mysterious host actually is. The latter does not openly appear, but instead communicates with the guests by radio broadcast. What he has to tell his guests is chilling: that every hour, one of them will die. Despite putting the guests on their guard, the Host’s prophecy starts to come horribly true, each demise occurring in bizarre fashion. As the dwindling band of survivors grows increasingly tense, their confessions to each other might explain why they have been chosen for this macabre evening-and invoke the nightmarish thought that the mysterious Host is one of them. The burning question becomes: will any of the party survive, including the Host…?’

Overall Thoughts

Gothic Roots

Perhaps this does not seem like the natural starting point for reviewing this book, but it was the place my own thoughts began, as I wondered what the roots were for this type of unknown killer operating within an enclosed space narrative. There is something decidedly gothic in its setup. In 2017 Michelle Miranda in her piece ‘Reasoning Through Madness: The Detective in Gothic Crime Fiction’ wrote that ‘the Gothic era dealt in fear and the unknown […] death, psychological degeneration, and mystery are the typical elements intertwined in Gothic literature,’ alongside ‘psychological terror, whether in the form of a monster or a madman.’ These components of Gothic literature, albeit repackaged, can also be found in Bristow and Manning’s tale. Fear is definitely a pertinent emotion for the characters who have many unknowns to battle, not least the unknown identity of their tormentor. Under such pressure psychological degeneration is not unlikely, and this certainly takes place in different forms in the narrative. There is also the issue of the psychological state of the person who is orchestrating these horrifying events. Degeneration of another kind can be found there, although in their defence they also take a strong swipe at the superficial nature of how society does or does not accept someone.

In Bristow and Manning’s story, the source of threat and danger comes from within their confined space. Whilst some Gothic influenced literature situated the unknown horror from without, i.e. it had to come in from the outside, such as in Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu’s Carmilla (1897), many posited the origin of the danger was closer to home. This is perhaps more the case when sensation fiction, a literary descendent of Gothic fiction, became more established. Judith Flanders in The Invention of Murder (2011) writes that ‘sensation-fiction implied a world in which every respectable person had a potentially unrespectable secret life.’ It is the people you are friends with, the people you thought you knew, who are the possible harbourer of danger. At the time this upended ‘the ideal of mid-Victorian domesticity’, according to Louis James in The Victorian Novel (2006). Importantly for us though these are threads which worked their way into Golden Age detective fiction and can be acutely seen in the type of setup Bristow and Manning create in their mystery. For example, in 1978 Elaine Showalter when discussing sensation fiction mentions how these texts suggest ‘the essential unknowability of each individual,’ and the characters in today’s read are keenly aware of this problem. Moreover, if they wish to survive the night, they are going to have to know each other a lot better, and fast.

What interwar crime fiction managed to do with these gothic and sensation fiction elements was to preserve the mystery for longer. With Victorian sensation fiction it can sometimes be easy to spot who the villain might be, even if they are not twirling their moustache. I don’t think there is much surprise when the villains are unmasked in Wilkie Collins’ The Woman in White (1859), for example, nor in Lady Audley’s Secret (1862) by Mary Elizabeth Braddon. Not so in Bristow and Manning’s book.

Another literary genre to consider in light of this novel is the ghost story, as the concept of an unknown killer, whose entry and exit upon the scene cannot seemingly be traced, was quite common in 19th century ghostly fiction. M. Grant Kellermeyer on the website Old Style Tales, has written a summary/analysis of Le Fanu’s ‘An Account of Some Strange Disturbances in Aungier Street’ (1851). The writer points out that ‘unlike most Victorian ghosts – Dickens’ for instance – Le Fanu’s is not seeking justice, equilibrium, or vindication; it is not a wronged soul, it is a wronging soul, gleefully collecting the corpses of its roommates and gathering nourishment from their terror – just as much a vampire as Carmilla.’ This struck a chord with me as I read Bristow and Manning’s mystery as the ‘host’ seems to operate more this way. After all that is why they design the murders to play out like a chess game. The way the killer manages to anticipate and predict the moves of the group equally gives the ‘host’ an unearthly and omnipotent quality.

Having gone into the underlying gothic mechanisms in Bristow and Manning’s novel, I would argue that more overt gothic overtones can also be seen in the text. Through the eyes of the youngest female guest we first see the apartment they have been invited to:

‘Facing her was a great door, heavily carved. There was something depressing about the dim light and the crooked shadows on the carving; she felt herself shiver as she crossed the hall and knocked. The door was so massive in appearance that Jean felt as if she was standing under a fortress. She lifted the heavy silver knocker, and almost immediately the great door swung back on stealthy hinges, as silently and as heavily as the door of a vault. A tall butler with white hair stood aside to let her pass.’

A semantic field of unease through looming and almost oppressive architecture is built up in this passage. Yet this is perhaps not the first nod to the gothic as Curtis Evans comments on the dustjacket artwork, ‘which depicted a ghastly scene of grey skyscrapers set against a night black background with a colossal red skeleton encroaching upon a bloodily lit penthouse atop one of the skyscrapers. It made a memorably grotesque and the hauntingly menacing panorama, like something out of Edgar Allen Poe’s “The Masque of the Red Death.”’ This is a sentiment I agree with, and it can equally be found in the little details of the location, such as the blood red glasses the guests drink out of.

There are two other tropes to consider with gothic roots. The first is the fate of being buried alive. At dinner, before the guests realise the horrors that await them, they mostly conclude that they do not wish to become old, that they might prefer to die at the pinnacle of their achievement. Yet when this seems to be a possibility, they rapidly change their minds and at one point Hank describes their situation as being ‘imprisoned […] as if we had been buried alive and had waked up in the tomb.’ This type of trope put me in mind of the likes of Edgar Allan Poe’s ‘The Premature Burial’ (1844) and Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897). The fact there are eight empty coffins on the enclosed patio and a body which falls out of a door only adds to the terror the characters face. Coming back to this ready-made corpse, the voice on the radio suggests they open the door to a hitherto unexplored room, and it is from this room that our corpse dramatically enters the scene. Rooms with sinister secrets are very much a staple of Gothic literature and a strong nod is given to them in Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey (1817) and Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre (1847). Bristow and Manning’s narrative utilises the device in a striking and tense fashion: ‘Sylvia turned the key. A sudden flare of lightning burst between the curtains and vanished with a thunderclap. They started. For a moment the rain beat at the windows, then the noise lessened and ceased. Sylvia’s hand was on the knob. The door swung open, and she sprang back with a face of unutterable horror. The body of a dead man fell into the room.’

Whilst I don’t opt to read gothic novels very often, I really enjoyed the gothic aspects in Bristow and Manning’s book. In particular I liked how they transplanted gothic tropes into a seemingly antithetical art deco apartment.

WARNING PLEASE ONLY READ THE CHRISTIE COMPARISON SECTION IF YOU HAVE READ BOTH AND THEN THERE WERE NONE AND THE INVISIBLE HOST

The Christie Comparison

Whilst it is quite common these days to claim that a modern writer is the “New Agatha Christie” or is “Christie like” – statements I find vastly and carelessly overused, I was intrigued to see how this book measured up as a predecessor to one of Christie’s most famous books.

The opening sequence in both titles offer some parallels as the chosen victims all receive a missive, including the killer, drawing them to the enclosed location. In Christie’s novel the reasons for bringing people to the island differ, some come for work, some for a holiday, others to be on the lookout for a murderer, but in Bristow and Manning’s mystery, all the guests are given the same telegram which makes them suppose a party is being held in their honour. Pride certainly comes before the fall in this case. The wording used in the opening sequence of The Invisible Host, put me in mind of Christie’s Roger Ackroyd linguistic clue as rather than saying this is what the characters think, the narrative says this is what the character will say when they go to the party. When you read this for the first time you assume that what the characters think/know is the same as what they say and therefore the killer is able to be mixed in amongst the victims.

Both texts also include a voice recording which reveals to the guests the terrifying trap they have walked into. However, I think the voice recording element is used more extensively in Bristow and Manning’s book, a touch I really liked. In Christie’s novel the recording is used to accuse the occupants of the household with past crimes they thought they had got away with, whilst in The Invisible Host, the voice recording is used to outline the rules of the sinister game set for them, as well as goad and torment them. In particular the recording often says when the next victim will die and who that victim will be. This gives the recording a greater sense of omnipotence and it ties back into the gothic ghost story element of not wanting to punish people for their failings, but to watch them squirm under the pressure. As such I think the voice in The Invisible Host is far more chilling and frightening, as for me they were more “present” in the events.

A key piece of deception in each story is that the killer tries to make themselves appear innocent by inflicting injury upon themselves. In The Invisible Host this is a flesh wound, which is more easily seen through, and is one of the reasons the criminal is unmasked. But in Christie’s mystery she takes this idea further by having the murderer convince another victim to falsely declare them dead and consequently I would say the deception in this instance is far more successful and leads up to a brilliant denouement.

Whilst there are some core similarities between the texts I think there are also some interesting differences. Firstly, unlike in And Then There Were None, the people trapped on the island do not all know each other, whilst in Bristow and Manning’s story they do. This previous knowledge adds to the disconcerting fear that they don’t truly know each other as well as they thought they did. Moreover, their past run ins with each other also means there are established lines of hostility and this feeds into the plot as often these grudges cloud the judgement of some characters. After all, at one point Tim says: “Every one of us knows […] that there’s somebody at this table whom he most particularly wouldn’t be found dead with.”

Secondly, I feel the setting used in The Invisible Host has a greater sense of claustrophobia and due to it being an apartment means that the group are more fixated on the idea that the killer is one of their own party, rather than an outsider. This differs to Christie’s story, as because it is an island, the idea that there could be an extra person on there is more feasible, so this option is considered for longer.

Thirdly, in keeping with the extra chilling voice recording, the manner in which people die in Bristow and Manning’s tale, is more sinister, in my opinion. This is because the methods deployed require the unwitting participation of the victim in order for it to be carried out. To this end the killer needs to predict much more how people will act, which contrasts with Christie’s story where there is perhaps an order for the killings, yet still some flexibility if needed. Gadgets are relied upon more in The Invisible Host too which makes sense given that the murderer must secure everybody within an urban building.

Finally, there is some difference in emphasis when it comes to who gets killed when. In Christie’s book the first to die is the one who regrets their actions the least and has the smallest capacity for comprehending their guilt. Conversely, in Bristow and Manning’s novel, because the killer has set up the idea of it being a game, their preference is to eliminate first those who they consider to be less worthy opponents.

Since this constitutes as a spoiler, I am going to conclude this section with why I did not give The Invisible Host a full 5 out of 5. It comes down to the fact that the narrative had two options as to how it could end and personally I think if it had chosen the path Christie took her novel down, then maybe it would have become the classic Christie’s did. It is such a Machiavellian book that a darker conclusion was needed to make it the perfect read.

The Characters

The success of this type of plot depends, to a degree, on how well-executed the characterisation is and fortunately for us Bristow and Manning are very good in this department. I felt we get a real sense of who the guests are in the opening sequence when they each receive their telegram. For example:

‘Mrs. Gaylord Chisholm tore open her yellow envelope with slim aristocratic fingers and read the message twice. A puzzled line came between her eyebrows, then she smiled amusedly. Under the pale lights of her boudoir Margaret Chisholm had the air of one of those ancient queens whose sculptured profiles look disdainfully down upon posterity. There was a gesture of empire in the very way she touched a flame to the end of her cigarette and held up the telegram to read it again through the blue plumes of smoke.’

There is a pleasing rhythm in the repeated narrative structure used as the guests receive their telegram and ponder who sent it and, in some ways, this rhythm has a cinematic quality. In addition, I also thought the characterisation of the voice on the recording was effective. Its entry into the story is perfectly timed and it was interesting to see that the guests have difficulty in pinning down the gender of it.

Murder as a Game

In mysteries such as Ngaio Marsh’s A Man Lay Dead (1934), the game murder is played, with unsurprisingly lethal results. Yet Bristow and Manning’s book took this concept to a whole new level several years earlier, upending murder as a game idea. Quite frankly they make Marsh’s novel appear anaemic in comparison. The killer in their novel hopes to present murder ‘as a social divertissement’ and is keen that their chosen combatants do not violate the rules they have devised, such as not leaving the flat and not disconnecting the radio. The killer “reassures” his victims there are no boobytraps, as they wish it to be ‘a game of skill.’ This point is possibly disputable though. The murderer also evokes a competition like element when they say, “I have flattered myself that I can win every round, so that as you lose, one by one, you must pay the forfeit. But if I lose—if one of you proves that he is cleverer than I, and outwits me, I promise you that the forfeit will be paid by me. If one of you outplays me at our game, I shall die in front of you all.” This promise to remove themselves is an intriguing twist and one wonders whether they will keep to their promise or whether they will need to.

Tension

Tension is fundamental if you want to write a suspense-filled mystery which keeps your readers on the edge of their seats. One such book I was reminded of when reading today’s review title, was Ethel Lina White’s Some Must Watch (1933). In both cases the action focuses on a single hair-raising night, a short time frame which racks up the suspense levels. Moreover, non-combatants are removed from the playing field through being drugged. This adds to the tension levels as it pointedly shows the remaining characters that help is nowhere in sight. Bristow and Manning are also a dab hand at atmospheric writing such as in the line: ‘The very room seemed to close in upon them, eight sane men and women against the wall of insanity, a ghostly voice whipping at their backs — “Before eleven, one of you, only one of you, my friends, will be dead.”’ The coffins I mentioned earlier are another example of tension levels being pushed to the max, as I felt their location of the patio created a chilling juxtaposition. Additionally, there is also a great moment when the group think they have beaten the voice, only to realise their group is one less. Suffice to say I did fear I might fall off my seat when reading this story, I was so much on the edge of it. Readers who have read Christie’s book don’t need to worry that the prior reading will hinder their enjoyment of this story, as there are plenty of surprises to be had, situated within a gripping and taut atmosphere.

Yet the fact this is novel could be classed as a suspense one does not mean it is lacking in clues or that there is no puzzle to figure out. After the latest eruption of tempers, when the group is beginning to disintegrate and fray, Dr Reid says:

‘“The reason we cannot think clearly,” he said, “is only partly that our faculties are numbed by horror at what we have seen and dread of what is to come. It is also that we are hampered by the interference of the person in this room who has planned our destruction. Whoever this person is, he is joining our discussion under the guise of contributing to it; he is inserting into it false clues to the mystery, throwing us everywhere off our guard.”’

This reminds us to not just experience the drama of the characters are going through but to also analyse it.

Ending

If you follow the advice in my last sentence, then maybe you will be able to figure out who is trying to bump off this group of people. I did not manage to do this myself, and I am currently nursing the bruises I gained from kicking myself when various clues are referred back to. I even noticed something, wrote a question in my notes, and then completely forgot to, you know, think about what it might mean. Yes, it was a face palm moment! However, I did anticipate one twist in the ending, so I don’t have to hand in my detective reader’s badge just yet.

So all in all this is a must read and I can heartily concur with Charles B. Coates, who reviewed the title for the Saturday Book Table Column, writing that:

‘The carnage we promise you is fascinating, and the denouement is startling, to say the least. Even the most hard-bitten mystery addict will be pleasantly puzzled, nay stumped, by this ingenious fictional device.’

Rating: 4.75/5

Source: Review Copy (Dean Street Press)

This sounds great, and I had no idea that Gwen Bristow wrote mysteries. I preordered it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes the introduction says she went on to write historical fiction. Is that how you came across her?

LikeLike

Yes. I have several of her historical fiction books on my TBR. Her historical fiction is all early American, including early California history. She was picked up and reissued by Open Road a few years ago, and my library happily has six of her reissues available for kindle.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Brilliant review, Kate! It’s been quite some time since I first read this one and you’re making me think I need to dig it out again. I enjoyed it very much when I did read it, but I think it’s been long enough that I might be fooled a second time. Have you seen the filmed version? I thought it was pretty good as well.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Glad you enjoyed it! And I shouldn’t be surprised that you have read this ultra rare book, though maybe it is less so in the US. It was never published in the UK, so that probably made it more scarce over here. I wanted to watch the film when I saw it had one but I can’t find it available anywhere. I can imagine this making a very good film.

LikeLike

The film is available in you tube.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh I didn’t know that. Thanks.

LikeLike

Indeed the film is an enjoyable way to spend an hour. The acting is wonderfully over the top, but I would expect no less from its era or the material.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for the review, which makes me eager for DSP to release it in just under a week! I skipped the part of the review where you made comparisons with ‘And Then There Were None’, but the rest of the review encouraged me to pre-order a copy on my Kindle. Is this the only title from the authors’ catalogue that DSP is releasing?

LikeLiked by 1 person

P.S. I enjoyed the gif featuring a surprised macaque… 🐒

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have not read anywhere that the other titles will be reprinted, but you never know. I look forward to seeing what you make of this one.

LikeLike

I also look forward to reading this one based on the strength of your review. Like JFW, I skipped over parts of your post until after I read it so nothing will be spoiled (although I have seen the film on Youtube already).

P.S. Agree that the animated GIFs are great. Hope the book triggers the same reaction in me.

LikeLiked by 1 person

So do I!

LikeLike

I managed to get my hands on Two and Two Make Twenty-Two at a book fair and enjoyed that one as well. I certainly hope that DSP (or someone, anyone) will look into reprinting The Gutenberg Murders and The Mardi Gras Murders–whenever I’ve seen those titles online the prices have been out of my budget. I would love to have a chance to read the last two of their four books.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fingers crossed someone will!

LikeLike

[…] comes out in January. Like with my earlier review this week of Gwen Bristow and Bruce Manning’s The Invisible Host (1930), I urge you to rush out immediately and buy or borrow this book, if you haven’t already […]

LikeLike

Thank you for the great review and article! I enjoy all the titles in the Mystery League series!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Glad you enjoyed my piece. Thank you for the link to the information concerning the Mystery League series. By the looks of it I have read four from the listing – The Invisible Host, The Secret at High Eldersham, Death Points a Finger and Death Walks in Eastrepps.

LikeLike

[…] The Invisible Host (1930) is a brilliant precursor to Agatha Christie’s And Then There Were None (1939). It is a perfect spine chilling read for October, with its nods to Gothic literature, which contrast with the 1930s New York setting. […]

LikeLike

I read this decades ago when I first discovered the Mystery League books. It sort of makes me laugh that this book is being touted as a discovery. The uncanny similarities to ATTWN have been written about ad nauseum all over the internet. Everyone who reads this book thinks no one else has ever heard of it or knows of the weirdly coincidental plot. I learned that when I talked about it at Mystery*File.

This new sensation proves to me how little anyone pays attention to the forgotten American writers of this era. It strikes me that the ATTWN connection has made it an irresistibly mercenary reprint idea considering the undying interest in Christie and her classic book. Overall I think it’s exceedingly inferior to Christie’s terrifying book, but nevertheless very fun as a pulpy thriller. The ending in INVISIBLE HOST is not handled well and is a huge disappointment to me

Does Curt discuss the Mystery League imprint in his intro? When I did my series on American mystery imprints five or so years ago I included the whole lot and tried to do it service because it had a bad reputation from most older mystery book collectors and readers. There are many more unusual, if not wholly original, novels in the Mystery League series. Some of them are definitely worth reading. But most of them are skippable. The other two books by Bristow & Manning sadly fall into the latter category.

LikeLike

Yes Curtis does provide information on imprint the book was originally published in.

LikeLike

[…] of Goddard’s book is very timely in one respect, as the Dean Street Press have reprinted The Invisible Host (1930) by Gwen Bristow and Bruce Manning, and this is a title Goddard discusses in his chapter on […]

LikeLike

[…] the novel itself. PD tossed it off with a few words. My friend Kate of Crossexaminingcrime, whose review came out a long while back, (so long ago that it might have been one of the book’s original […]

LikeLike

Great review Kate, and so thorough! Like you, I really loved this novel. I think Christie’s setting makes it easier to avoid all the elaborate reasons why various escapes don’t work, and The Invisible Host lost some of the neat simplicity, but overall I thought it was brilliant and I truly raced through it. I’m pretty sure I’ve never successfully identified a twist or a murderer, and try not to think too much in case I spoil it for myself, so safe to say I was caught out!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks. Glad you enjoyed the book also. I thought it was interesting went for an urban setting rather than a more isolated rural one – the writer took on different challenges by doing so.

LikeLike

Oh, and I watched the film the other night – quite pared down and simpler, which makes for easier watching though means a few contrivances and coincidences are left in, and it cuts my favourite twisty moment.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I can see why they might have had to simplify the story for film but I definitely found the adaptation wanting.

LikeLike

[…] good read. And – in a moment of extreme irony – I would urge you before you vote to read Kate Jackson’s review of the book from September because she LOVED this one. She might even have you thinking long and […]

LikeLike

I have purchased this book following your review and just finished it. I was amazed with it, what a gem!! They knew how to write them in those days. It also reminded me how much I like gloden-age books more than modern crime novels. For example, I have recently acquired a book with premise similar to Agatha Christe “Ten little indians”. I fell for the blurb and off course, it was a dissapointment. Thank you for this wonderful review!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Glad you enjoyed the review and more importantly the book itself.

LikeLike

[…] first encountered this writing duo last autumn when I reviewed The Invisible Host (1930). A book I very much enjoyed, so I was keen to try another by them. As with the other book, […]

LikeLike

[…] No. 1 – The Invisible Host (1930) by Gwen Bristow and Bruce […]

LikeLike

[…] how much book group had independently enjoyed Gwen Bristow and Bruce Manning’s The Invisible Host (1930) (winner of the Reprint of the Year awards 2021), everyone was keen to try together another […]

LikeLike

Thanks for this review. When I saw the address on Ursuline Street, I knew it must be set in New Orleans, one of my favorite cities in the world. I haven’t run across many GAD-era mysteries set there, so I’m excited to read this one.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s nice when a mystery includes a part of the world we are familiar with or love. I think that is why Lorac’s books have been so popular. Hope you enjoy this one.

LikeLike

[…] No. 3: The Invisible Host (1930) by Gwen Bristow and Bruce […]

LikeLike

I’m so eager to start it (later on today). Come to think of it, maybe I added it to my TBR when I read your review. I’m so intrigued about the comparison with Christie’s book. But I skipped reading that part for now, I’ll come back to read it after I’m done with my own thoughts on the comparison. Thanks for this very detailed review

LikeLiked by 1 person

I look forward to seeing what you make of it!

LikeLiked by 1 person