I was long overdue a return to the work of Vaseem Khan. I still remember fondly the surreal scene in The Unexpected Inheritance of Chopra (2015) in which the eponymous sleuth must lure a baby elephant up a shopping centre escalator. However, today’s read comes from Khan’s latest series starring Inspector Persis Wadia, which is set in 1950s India. Wadia is described as being ‘India’s first female police detective’ and I was curious as to the history of policewomen in India.

Shamim Aleem’s 1989 article, ‘Women in Policing in India’ notes that:

‘Although women entered the India police as early as 1938, their growth and development have been slow. For the most part, women were used as social workers rather than as law enforcement officers, dealing mainly with matters concerning women and children.’

This is an idea corroborated by Dr V. Rajeswari and Dr A. Alagumalai whose 2017 article ‘The Origin Role of Women Police in India’ mentions that the creation of female constables and special constables was partially influenced by strikes in which women obstructed building entrances by lying down in front of them. Nevertheless, the early years of policewomen seems to have been a series of units being formed and then disbanded or absorbed into other government organisations. I was also interested to learn that Kiran Bedi ‘became the first woman in India to join the officer ranks of the Indian Police Service in 1972’ and Bedi is reported as having said: ‘At the time, I didn’t know that I was going to be the first woman in India to join the police officer ranks of the Indian Police Service. I didn’t join to be the first. I became the first, it happened to be like that.’ I am curious as to whether Bedi was an influence on the character of Inspector Wadia. Nevertheless, I think Khan has chosen a vibrant and engaging part of history within which to set his series and he writes in a way that encourages you to go away and find out more about the period.

Synopsis

‘Bombay, New Year’s Eve, 1949

As India celebrates the arrival of a momentous new decade, Inspector Persis Wadia stands vigil in the basement of Malabar House, home to the city’s most unwanted unit of police officers. Six months after joining the force she remains India’s first female police detective, mistrusted, sidelined and now consigned to the midnight shift. And so, when the phone rings to report the murder of prominent English diplomat Sir James Herriot, the country’s most sensational case falls into her lap. As 1950 dawns and India prepares to become the world’s largest republic, Persis, accompanied by Scotland Yard criminalist Archie Blackfinch, finds herself investigating a case that is becoming more political by the second. Navigating a country and society in turmoil, Persis, smart, stubborn and untested in the crucible of male hostility that surrounds her, must find a way to solve the murder – whatever the cost.’

Overall Thoughts

Detectives in fiction can be portrayed as outsiders or as being marginalised in some way and Persis Wadia, being the lone female police detective, certainly seems to fit that category. This is reinforced by the unit she was sent to work in at Malabar House, as the story says the people who worked there ‘were outsiders, brought together precisely because they had been deemed unfit for any assignment of worth.’ Persis’ status as an outsider also comes through in the way her personality is contrasted, at the beginning of the novel, with the end-of-the-year-party atmosphere most of Bombay are indulging in: ‘Frivolity was alien to her nature and she had often been told that her tastes – in matters of dress and deportment – tended to be staid.’

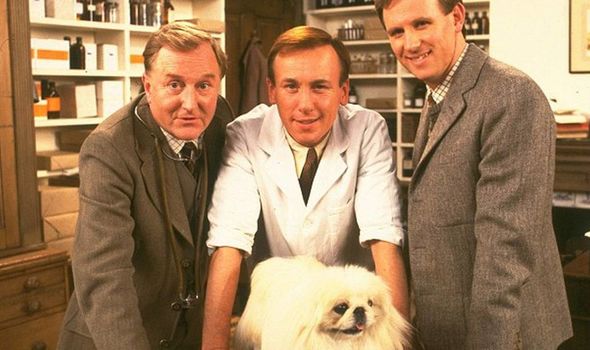

The opening pages set a good pace with a phone call promptly reporting the central murder and I liked how this small incident is used to depict the prejudice Wadia receives, with the caller using the word ‘Miss’ rather than ‘Inspector’. The first chapter also introduces the name of the victim, Sir James Herriot and I must admit this did cause a bizarre moment in my brain where I was wondering why James Herriot the Yorkshire vet had been knighted and gone to India.

My own silliness aside character names sometimes arguably carry further meaning in this story. The character I most had in mind was Archimedes Blackfinch a.k.a. Archie, who is a criminologist and an advisor to the crime branch in India, having been seconded from the Metropolitan Police. I thought his first name was an interesting choice. It fits in with his job role as an “expert”, but I also wondered if it was meant to suggest that Archie is something of an anachronism. Archimedes is associated with ancient Greece when it was a world power before the Romans took over, so consequently, as a British character, are we supposed to read Archie as representative of a different world power which was also declining?

Nevertheless, I was intrigued by the comment Sir Herriot’s chief aide, Madan Lal, makes when explaining to Inspector Wadia why Archie has been called into assist with the case:

“As you know our government is keen to breathe new life into the various state organs that have been returned to our patronage. If India is to uphold the rule of law we must have a police force worthy of the name. Advisors such as Archie have been retained to provide us with the necessary rigour to underpin our ambitions.”

It sounds like Lal is suggesting that in order to achieve the goal of independence, India must first get help from the nation they are seeking independence from. Unsurprisingly this idea creates tension and friction within the novel, and I think this is an example of how the author describes the Partition and its consequences. Khan doesn’t write about this period of history in simplistic and reductive terms.

This is also seen in the narrative when Inspector Wadia is at the police station, as we can see the antagonism between Persis’ colleagues and how this exemplifies the social tensions caused/aggravated by the Partition:

‘Hindu and Muslim were ostensibly equals in India, but the truth was that the bitterness instigated by Partition still echoed in the hearts of millions across the country.’

Moreover, as Persis investigates Sir Herriot’s murder, it is shown that it could be linked to the commission he had recently been given, investigating atrocities committed during the Partition process.

Historical novels can sometimes suffer from info-dumping, as the writer tries to establish what it was like to live in that time period and to bring up relevant and interesting facts. The result can lead to a slow and boring read, as the historical research risks holding up the plot. However, Khan does not have this problem, as he is skilled at weaving interesting historical points into the fabric of his story. An example of this is that the fingerprint system known as the Henry Classification System (after Sir Richard Henry) was actually developed by two Indian police officers called Azizul Haque and Hem Chandra Bose. Sir Henry had been their supervisor and had received the full credit for this invention. To read more about this, here is a link to Khan’s website in which he explores this situation in more detail.

I think the way Archie is introduced into the story, leaves you more firmly on the side of Persis Wadia. Archie is not made to be completely unlikeable, but he is shown to be thoughtless and inconsiderate such as ‘not bothering to explain’ what he is doing when he is examining the crime scene. He also bags up an item for testing, without telling Wadia what it is. The beginning of the investigation is good at showing the obstacles Wadia is up against when simply trying to just do her job. Figures such as Archie keep her in the dark at the times, although without Archie’s presence Inspector Wadia may have struggled to have obtain permission from Lal to question the well-to-do guests at the victim’s new year’s party. Archie has the ability to “open doors”, yet I think these moments help you to sympathise with Persis, as she shouldn’t need the presence of a white male for her to fulfil her duties as a police officer.

Interestingly, Archie does not have as much page space as you might imagine as after investigating the crime scene in chapter two, he is off the page for quite some time. I would describe his appearances in this novel as sporadic. I can see why this had to be the case, as it is important for Persis Wadia to take centre stage and to direct the course of the narrative and for us to see India through her eyes. It would have been a much poorer book if Archie had taken over. However, due to his limited appearances and the small contributions Archie makes to the case, I was left wondering how much he really adds to the story. Does Wadia really need him, was a question I asked myself as I read this mystery. Or is that the point being made? I am curious as to how his role plays out in later books in the series.

I felt the delivery of the solution was longer than it had to be, as it had too much repetition of information, as after the relevant parties share their pieces of the puzzle, and we get a confession from the killer, we then get a long summary of all this information again immediately afterwards by Wadia. It is common for the investigating officer to tell a group of a suspects the solution to the case, but within this narrative structure it was robbed of its potential to surprise, and it was rather redundant. However, I did enjoy the interesting reversal of gender roles in one part of the denouement.

Rating: 4.25/5

What a lovely, nuanced analysis of the book – I really do like this series (although the latest one felt just a tad weaker).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you!

LikeLike

indian crime novel? well, i accidentally picked up “the perfect murder” by H.R.F. (“henry”) keating — as an audible audio book, with a reader who could do a pretty nice goon show type indian accent — so i had to go and get eight more books by the same author. obviously.

tom appleton

>

LikeLiked by 1 person

I can’t remember if I have read that one by Keating.

LikeLike