Today, it has been five years since I first began writing this blog. How much has changed! I almost feel embarrassed by my early reviews. (Cue everyone searching to read how bad they were). To date I have managed to rack up 1133 posts and 1191808 words. You will probably laugh at the idea that I had a lot of second thoughts about starting my blog. After all, what would I have to say? (Yes, please stop laughing now, you might choke on your tea/coffee…)

I spent a lot of time wondering what to write about for this anniversary post and in the end I became inspired when I read that Anthony Berkeley dedicated Trial and Error (1937) to P. G. Wodehouse. A little more internet searching and I discovered that many other well-known classic crime writers had done the same thing: Agatha Christie’s Hallowe’en Party (1969), Edgar Wallace’s The Ringer (1926) and A King by Night (1925), as well as Leslie Charteris’ Saint’s Getaway (1932) and E. Phillips Oppenheim’s Up the Ladder of Gold (1931) – and I wouldn’t be surprised if there were more examples. I also learnt that Wodehouse even played golf with Arthur Conan Doyle!

P. G. Wodehouse was known to have been a fan of detective fiction[1], so much so, that when John Dickson Carr began publishing his Sir Henry Merrivale mysteries, under the name of Carter Dickson, it was supposed in some quarters that the penname was for Wodehouse. However, crime did find its way into some of Wodehouse’s own writing[2], including into some of his Jeeves and Wooster and Blandings Castle stories. Twelve examples are also contained in the collection Wodehouse on Crime (1981), which I have read, albeit many years ago. From thefts,[3] bank jobs[4] and airgun shootings[5], to cons[6] and blackmail[7], crime finds its way into Wodehouse’s oeuvre. Yet today I will be looking at matters the other way around – How did Wodehouse’s work shape and influence classic crime literature?

Like dropping a stone into a pond, the ripples were numerous…

In Wodehouse’s fictional worlds criminal acts are mostly treated in a light-hearted manner, with no fear of a lengthy prison sentence. Thefts and pranks are the order of the day, with breaking the law becoming more of a game. Characters may undergo uncomfortable situations, like Bertie Wooster, yet there is invariably little sympathy for their suffering from other characters. Perhaps the suffering is taken less seriously because it is never of a permanent  nature. This is a mood, in part, which was transposed, at times, to the solving of crimes in interwar detective novels.

nature. This is a mood, in part, which was transposed, at times, to the solving of crimes in interwar detective novels.

This lightness of mood can be seen particularly in detective novels which are set at country house parties; Wodehouse’s natural hunting ground. In Ngaio Marsh’s Enter a Murderer (1935), murder quite literally becomes a game, whilst in keeping with many of Wodehouse’s tales the awkward or hostile collection of dinner or house party guests also makes its home within detective fiction. In one short story[8] C. A. Alington even has a character say that their host ‘has no idea of choosing his guests to match one another’ and when it comes to Marsh’s Death and the Dancing Footman (1941), the host in question goes all out to make sure his guests are as antagonistic as possible to one another.

Country houses, in fiction at any rate, are also vulnerable to imposters. Wodehouse once said that ‘without at least one imposter on the premises, Blandings Castle is never itself’ and in the likes of Something Fresh (1915), the debut novel of this series, there are two of them after a valuable Egyptian amulet. There are many examples of mystery fiction of the 20s and 30s utilising this trope as well, such as Christie’s The Murder at the Vicarage (1930), where a thief poses as an archaeologist to steal silver from the Protheroes.

Overall, I would say that P. G. Wodehouse’s stories really cemented the idea that it was okay, and that it could be highly effective, to write a crime story comically[9], and not just as a Holmes parody. This post will hopefully touch on how this is achieved.

Men are from Mars, Women are from Venus

Much of Wodehouse’s comedy is based on the mingling of the sexes. Love certainly gets his characters into an awful lot of bother! The path to marriage is never straight and courtship can be a rather tumultuous ride. Part of Wodehouse’s treatment of this theme concerns the power play between men and women, and invariably the latter are shown to have the upper hand and be firmly in the driving seat. This is so much a part of his style that when mystery writers of the era copy it, it quickly reminds you of the original.

Some examples include two of Christie’s Tuppence and Tommy Beresford short stories from the collection, Partners in Crime (1929). The first is ‘A Pot of Tea’ (1924) in which Lawrence St Vincent asks the Beresfords to help him find Janet, the woman he loves. Yet the solution to this mystery reveals that Janet is Tuppence’s good friend and that Janet’s staged disappearance was engineered between the two women to provide good publicity for the detective agency and to push St Vincent into proposing to Janet. This type of comically portrayed manipulation very much puts a Wodehouse stamp on the piece, and in keeping with Wodehouse’s style, there is no real censure given for such behaviour.

The second story is ‘The Unbreakable Alibi,’ (1928) in which the Beresfords are engaged to help a rich, but not terribly bright, young man called Montgomery Jones. Like many of Wodehouse’s male characters Jones falls instantly in love with a woman, (Una Drake), who he barely knows, and she has made a bet with him. Una gives him two alibis for a specific day, and he has to decide which alibi is fake. If he wins, she says he is allowed to ask her any question he wants, and naturally he wants to propose to her. Una is shown to be far brainer than him, and very much in control of the situation and when the Beresfords discover the truth, it is clear she is not especially in love with Jones and is far more interested in playing a joke on him. Una would definitely not be out of place in Wodehouse’s catalogue of characters.

Anthony Berkeley was another writer who incorporated the Wodehouse depiction of romance into his work. The  biggest example of this can be found in his parodic thriller Mr Priestley’s Problem (1927), which is propelled by a battle of the sexes. Like many a Wodehouse male protagonist, Mr Priestley faces unreasonable female demands and acquiesces in true Wooster fashion. Early in the story Mr Priestley finds that the woman he has met, incorrectly thinks he is the burglar she has hired, and even when he tries to correct her, she is keen for him to help her anyways, regardless of his lack of professional skills. Rather than showing her the door, so to speak, Mr Priestley’s takes a different approach:

biggest example of this can be found in his parodic thriller Mr Priestley’s Problem (1927), which is propelled by a battle of the sexes. Like many a Wodehouse male protagonist, Mr Priestley faces unreasonable female demands and acquiesces in true Wooster fashion. Early in the story Mr Priestley finds that the woman he has met, incorrectly thinks he is the burglar she has hired, and even when he tries to correct her, she is keen for him to help her anyways, regardless of his lack of professional skills. Rather than showing her the door, so to speak, Mr Priestley’s takes a different approach:

‘It appeared to him with sudden and unexpected force how remiss it was of him not to be a burglar. It was not playing the game. Here was this charming girl expecting to meet her burglar, never dreaming that she was doing anything else but meet her burglar; and there was Mr Priestley going about the place not being a burglar at all. His conduct had been despicable; that was the only word for it – despicable!’

This misguided, shall we say, thread of logic put me in mind of one of the proposals Bertie Wooster receives in Right, Ho Jeeves (1934). Well I say proposal, it is more of an order really…

“… I can never forget Augustus, but my love for him is dead. I will be your wife.”

Well, one has to be civil.

“Right ho,” I said. “Thanks awfully.”

Returning to Mr Priestley’s Problem, the plot is naturally propelled along a certain path because of this excessive chivalry and whilst Berkeley has a troubled attitude towards women, in this particular instance the text seems to imply that whatever goes on to happen to Mr Priestley, is exactly what he’s asked for and deserves!

Berkeley also touches upon female power in Panic Party, in which Mr Pidgeon disagrees with Roger Sheringham’s belief in women being the weaker sex: ‘I don’t agree that the weaker spirits and the women should be classed together […] If you imply that the words are synonymous, I agree still less.’ The typical Wodehouse couple, in this book, can unsurprisingly be found in the youngest two characters, Unity Vincent and Harold Parker. Initially Unity appears to be demure and shy, someone who couldn’t possibly say boo to a goose. But once she begins talking to Harold it is soon the case that he is ‘under her wing,’ and it is not long before she insists that Roger helps Harold to write up his film scenario. She automatically assumes the help will be given and talks over the top of any suggestions that Roger may not have the expertise or experience to provide it. Just in case we’re not convinced that she is the one wearing the trousers in the relationship, we get lines such as: ‘That’s enough Harold […] I’ve told you before not to overdo the thanks.’ (She has literally only known him for a couple days…)

The Aristocratic Sleuth

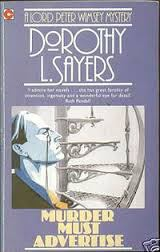

Wodehouse’s tales invariably move in affluent, socially mobile and aristocratic circles and I think this influenced subsequent detective fiction in different ways. Bertie Wooster, one of Wodehouse’s most well-known characters, provides a fundamental blueprint for upper class protagonists. A strong example of one of Wooster’s literary  descendants would be Dorothy L. Sayers’ Lord Peter Wimsey, particularly in his cases from the 1920s. Although a character in Murder Must Advertise (1933) does describe Wimsey as being ‘like Bertie Wooster in horn rims.’ Generally, I would say Sayers and Wodehouse’s work often swam in similar class waters and both shared a fondness for a Latin quotation, though I imagine Wimsey is more accurate than Wooster in that regard… Then there is of course the gentlemen’s club. For Wooster it is the Drones club, whilst with Wimsey it is the Egotist’s Club[10] and the Marlboro[11]. In fact, Sayers even situates a suspicious death at a club in The Unpleasantness at the Bellona Club (1928). Another example of this that I found was in J. J. Connington’s The Dangerfield Talisman (1926), in which the Romarin club is mentioned, and the opening of this tale does feature gentleman’s club type banter. As Wodehouse’s fiction attests to, gentlemen’s clubs tend to propagate pride fuelled ludicrous bets. Arguably the most unusual bet Wooster gets involved in can be found in ‘The Great Sermon Handicap’ (1922), in which he and various others back different ministers. The person who wins is the one who has chosen the minister who preaches the longest sermon. Bets between gentlemen also occur in interwar detective fiction, with Poirot’s bet with Monsieur Giraud of the French police in Murder on the Links (1923) springing to mind.

descendants would be Dorothy L. Sayers’ Lord Peter Wimsey, particularly in his cases from the 1920s. Although a character in Murder Must Advertise (1933) does describe Wimsey as being ‘like Bertie Wooster in horn rims.’ Generally, I would say Sayers and Wodehouse’s work often swam in similar class waters and both shared a fondness for a Latin quotation, though I imagine Wimsey is more accurate than Wooster in that regard… Then there is of course the gentlemen’s club. For Wooster it is the Drones club, whilst with Wimsey it is the Egotist’s Club[10] and the Marlboro[11]. In fact, Sayers even situates a suspicious death at a club in The Unpleasantness at the Bellona Club (1928). Another example of this that I found was in J. J. Connington’s The Dangerfield Talisman (1926), in which the Romarin club is mentioned, and the opening of this tale does feature gentleman’s club type banter. As Wodehouse’s fiction attests to, gentlemen’s clubs tend to propagate pride fuelled ludicrous bets. Arguably the most unusual bet Wooster gets involved in can be found in ‘The Great Sermon Handicap’ (1922), in which he and various others back different ministers. The person who wins is the one who has chosen the minister who preaches the longest sermon. Bets between gentlemen also occur in interwar detective fiction, with Poirot’s bet with Monsieur Giraud of the French police in Murder on the Links (1923) springing to mind.

However, perhaps the most extensive legacy Wooster and his cohorts have given classic crime fiction is a manner of speaking. Who doesn’t think of Wooster when a character says ‘what ho!’, ‘bally,’ ‘jolly good chaps,’ ‘dash it’ and ‘I mean to say.’ In some novels you are not surprised to find a character talk in this way, but I certainly did not expect to find it in John Dickson Carr’s Castle Skull (1931). A character nicknamed the duchess talks in this jocular fashion when she first encounters the sleuths saying things such as, “What ho!” and “My hat, another detective! The place is infested with detectives. You ought to get up a musical comedy, you know; male chorus singing “The Sleuth Stomp” or “My Derby and Me.”’ Interestingly this is a style of speech which finds its way even into later novels such as Thurman Warriner’s Death’s Bright Angel (1956)[12]. Unsurprisingly Lord Peter Wimsey’s speech is also peppered with Wooster-isms. In particular he embodies Wooster’s tendency to use speech disfluency features such as filler phrases. Wimsey’s first meeting with Harriet Vane in Strong Poison (1930), exemplifies this well:

“You are Lord Peter Wimsey, I believe, and have come from Mr Crofts.”

“Yes. Yes. I — er — I heard the case, and all that, and — er– I thought there might be something I could do, don’t you know.”

“That was very good of you.”

“Not at all, not at all. Dash it! I mean to say, I rather enjoy investigating things, if you know what I mean.

This social setup would also not be complete without our gentleman’s valet or butler, with Wooster’s Jeeves and Wimsey’s Bunter, heading the mental list. In fact, Sayers’ duo directly comment on their literary ancestors in Strong Poison. At the close of the mystery there is this interaction between the pair:

“Pardon me, my Lord, the possibility had already presented itself to my

mind.”

“It had?”

“Yes, my Lord.”

“Do you never overlook anything, Bunter?”

“I endeavour to give satisfaction, my Lord.”

“Well then, don’t talk like Jeeves. It irritates me.”

Returning to Wooster’s manner of speech, sometimes a comparison can even be mentally made when the character does not use the same phrases as Wooster but constructs their sentences and describes things in the way you would expect him to. I have found this to be the case with the work of Alan Melville. For example in Weekend at Thrackley (1934), Jim Henderson, tongue in cheek, tries to write out a job advert for himself: ‘pleasant and extremely good looking young man, aged thirty-four, possessing no talents or accomplishments beyond being able to give an imitation of Gracie Fields giving an imitation of Galli-Curci, with no relations and practically no money, seeks job.’ To which he reflects ‘that the subject of the sentence was much too far away from the verb to make the thing at all pleasant to the ear.’ Then in Death of Anton (1936) we have exchanges such as this, between Detective Minto and the waiter:

“Grapefruit… or Porridge?”

“What’s the name of the chef?”

“Bernstein sir.”

“In that case, grapefruit… If it had been McKenzie or McDonald, we might have risked the porridge. Being Bernstein, we’ll have the grapefruit.”

I think one of Wodehouse’s biggest strengths was giving his characters such an identifiable and memorable way of talking, that one can hear an echo of it in so many subsequent books by other authors.

Aunt Power

Although gender has already been discussed, I felt aunts needed a section of their own. Alongside the aristocratic gentleman, another intrinsic figure in Wodehouse’s fictional worlds is the middle aged or elderly aunt. These women  hold considerable power over the lives of their nephews, and invariably expect their whims and plans to be adhered to, regardless of the scrapes they land their relations into. Wooster finds himself in more than one tight corner due to the machinations of his aunt Dahlia.[13]

hold considerable power over the lives of their nephews, and invariably expect their whims and plans to be adhered to, regardless of the scrapes they land their relations into. Wooster finds himself in more than one tight corner due to the machinations of his aunt Dahlia.[13]

Difficult aunts made their home in interwar crime fiction too and the work of Berkeley provides us with another good example, as one of his minor serial characters, Ambrose Chitterwick, has a formidable aunt, and in The Piccadilly Murder (1929), despite him being a competent amateur sleuth, we are told that:

‘one of the most important men in the country started violently and quickened his pace almost to a run. He had undertaken to be back in Chiswick with the curtain patterns for his aunt by half-past nine.’

Aunts also crop up in Berkeley’s Panic Party, in which Unity opines that aunts are unpredictable and potentially dangerous figures; a dimension crime fiction of the era explored quite fully. Both of those adjectives could also be applied to great aunt Puddiquet in Gladys Mitchell’s The Longer Bodies (1930), where she certainly rules the roost over her relations. At the start of the book she has decided to leave her fortune to whichever male relative demonstrates the most potential in a given Olympic sport, (a potential to be proven at her homemade Olympics.) However, the most dangerous aunt of classic crime fiction can perhaps be found in Richard Hull’s The Murder of my Aunt (1934). In this story an aunt and nephew are very much at logger heads with one another, with the nephew’s desire for a soft urban life clashing with his aunt’s insistence he earn his own living and get some exercise. Maybe the underlying aims of the aunt are more sympathetic than those found in Wooster’s, but her methods of achieving them are perhaps more questionable. Time after time she bests her nephew as he tries to do things his way, yet you may think she has pushed him too far when he begins to plan her demise…

Being Good, Looking Bad

Whilst researching this post it became apparent to me that young gentlemen, such as Wooster, in Wodehouse’s fiction spend a prodigious amount of time getting others out of messes or trying to extricate themselves out of them, having tried to help somebody else in the first place. Their actions invariably self-incriminate, regardless of the fact that their aims were benevolent and well-intentioned. Sometimes these sticky situations and their methods for freeing themselves from them have the unfortunate tendency to make them look like criminals or cads. Night-time antics play their part in this trope, and naturally these circumstances which are highly uncomfortable for the participants, are great fun for us to read.

Yet in the hands of golden age crime writers this trope gains heightened peril, as the self-incriminating actions can very often make it appear as though that person did the murder! The Dangerfield Talisman (1926) by J. J. Connington contains such an example with his hapless heroine condemning herself with her silence, as it is pointed out that she was seen wandering around the house that night for no obvious reason. Was she visiting the bachelor’s wing or was she stealing the talisman? Neither reason makes her look good, though her reason, which is eventually told, shows good intentions. A. A. Milne’s Four Days Wonder (1933) equally has a female protagonist in a tricky situation. In a breezy Wodehouse style the book begins like this:

‘When, on a fine June morning not so long ago, Jenny Windell let herself in with her latch-key at Auburn Lodge, and, humming dreamily to herself, drifted upstairs to the drawing-room, she was surprised to see the body of her Aunt Jane lying on a rug by the open door. It had been known for years, of course, that Aunt Jane would come to a bad end.’

Yet unfortunately for Jenny, she only realises it is murder once she has cleaned and replaced an item on the piano. On hearing the people renting the house return she naturally makes her escape through a window and leaves a bloodstained and monogrammed handkerchief and a footprint. The rest of the story is her madcap bid to stay one step ahead of the law, and her temporary sufferings and deprivations invariably evoke amusement rather than anxiety on the part of the reader.

Being found in a room or place that you should not be in, is endemic for Wodehouse protagonists.[14] For instance, in Jeeves and the Feudal Spirit (1954), it seems that Aunt Dahlia has pawned her pearl necklace, given to her by her husband, in order to fund her magazine. Yet an expert is coming to their home and she fears they will reveal that the one she has is an imitation. To help her out Wooster is cajoled into stealing the fake, so it cannot be assessed. But of course this goes horribly wrong. Wooster enters the wrong room and is found in Florence’s bedroom and the person who finds them is her ex-fiancé, who broke up with her because he heard Wooster had taken her to a night club. (The fact Florence forced Wooster to take her there for colour for her next novel is disregarded.) Wooster definitely does not across in a good light at this point! A similar difficulty of being found in the wrong bedroom is also faced by a character in C. A. Alington’s ‘The Adventure of the Dorset Squire’ (1931) and in Richard Shattuck’s The Wedding Guest sat on a Stone (1940) the female lead has the added horror of realising she has got into a bed with a corpse! A misinterpretation of events naturally follows moments such as this, with the unsavoury theory being favoured by bystanders or anticipated by the character in question. In Wodehouse’s books this is purely done for entertainment value, but in crime fiction I think it also has the additional purpose of obscuring the truth about a crime and can therefore be used as a red herring for the reader, who is led to believe one thing when actually something else has been going on.

Often characters such as Wooster cannot reveal their real reasons for doing something or being somewhere and one of the reasons for this is chivalry, with their silence on the matter covering up for a woman’s actual or perceived incriminating behaviour. Crime fiction from the time period makes good use of this device appearing in works such as J. Jefferson Farjeon’s The Z Murders (1932) and Christopher Stjohn Sprigg’s Fatality in Fleet Street (1933). It is not uncommon either for these men to have no concrete proof of their lady’s innocence of the bigger crime of murder, (though they may be guilty of a smaller one), and it seems as though they are going on faith, gut feeling or the fact that they are strongly attracted to the woman – after all anyone they fall in love with surely isn’t the culprit!

Anyone who has read Wodehouse’s work will be familiar with the intricate and tight plotting of his narratives, particularly with his Wooster and Jeeves tales. Early events act like snowballs, with greater and greater difficulties developing, until someone, usually Jeeves, has to save the day, and the schemes masterminded and acted upon to  resolve the predicament are often entertainingly elaborate and involute. This style of plotting is utilised to the maximum in Alice Tilton’s eight book series starring Leonidas Witherall.

resolve the predicament are often entertainingly elaborate and involute. This style of plotting is utilised to the maximum in Alice Tilton’s eight book series starring Leonidas Witherall.

Mistaken or assumed identities are one factor which place characters into this type of hot water. Perhaps a character is just trying to fill in for someone, or maybe they just didn’t have the confidence to correct someone who mistakes them for another. Either way things escalate detrimentally for the character concerned. This narrative arc is one which occurs a number of times in the Witherall series, particularly in The Left Leg (1940) and The Cut Direct (1938). This also happens on a regular basis to Wooster, such as in The Mating Season (1949). In that story Wooster pretends to be his friend Gussie, in order to prevent Gussie’s fiancée Madeline Bassett from realising that he is in prison for 14 days. If she finds out she will break off the engagement and will then marry Wooster – a fate Wooster really wants to avoid. This simple plan though quickly goes awry and things begin to get rather  complicated. Gussie turns up pretending to be Bertie and at one point Gussie even changes his mind about marrying Madeline. Meanwhile in ‘Without the Option’ (1925) Bertie has to stand in for another friend who has got himself sent to prison for a short spell, when he ought to be staying with unpleasant friends’ of his aunts. Once more Wooster ends up in yet another debacle.

complicated. Gussie turns up pretending to be Bertie and at one point Gussie even changes his mind about marrying Madeline. Meanwhile in ‘Without the Option’ (1925) Bertie has to stand in for another friend who has got himself sent to prison for a short spell, when he ought to be staying with unpleasant friends’ of his aunts. Once more Wooster ends up in yet another debacle.

Aside from the work of Alice Tilton, many other classic crime writers used this premise to begin their comic crime novels. Another strong example can be found in The Black Coat (1948) by Conyth Little. In that story there are two women heading to New York on a train and they are both called Anne. Our protagonist is going to find work as a commercial artist. The second Anne is an unreliable party girl, who takes the other woman’s coat, leaving her own, and gets off at an earlier station. Wearing the incorrect coat Anne is greeted by the wrong person, who identified her by a flower in her buttonhole, and is taken to visit the other woman’s sick grandmother. From here on in our protagonist’s troubles multiple, with strange goings on in the hotel and a murderer to avoid to boot!

Same Problems, Different Solutions

Whilst this post has mostly been looking at the similarities between Wodehouse’s work and classic crime fiction, this final section changes tack slightly, as I wish to explore how Wodehouse’s characters and the characters in mystery novels often share the same problems, yet they can take very different approaches to solving them.

More than one Wodehouse character has had a difficult patriarch or matriarch to deal with, who either holds the purse strings or is blocking their chance to marry someone. One example of this can be found in ‘Jeeves in the Springtime’ (1921) where Wooster’s friend Bingo is determined to marry a waitress called Mabel, but his uncle will not approve and may even stop his allowance. Solution? Jeeves has Bertie read to the bed-ridden uncle, (he has bad gout), many romance stories which positively depict inter-class marriages. Yet such a novel solution is not the kind to be adopted in a detective story. In fairness when it comes to mystery novels of the era, the motive of murdering a relative so they cannot forbid you marrying someone, is usually a red herring, such as in Death in the Stocks (1935) by Georgette Heyer, (hope my memory has served me well here!) However, occasionally a writer does show the drastic lengths a woman will go to, to get the man they love. Murder on the Links is an early example of this.

A lack of money is another common problem. Detective novels in which murder is committed for monetary gain are plentiful, contrasting with the creative non-murder options Wodehouse’s characters come up to solve the same issue[15]. However, another crime which links both Wodehouse’s fiction and classic crime novels is theft and in particular attempts to steal and destroy memoirs which will expose many secrets. Both Heavy Weather (1933) and ‘Jeeves Takes Charge’ (1916) include this plot line, though naturally these are more comically toned than say Ngaio Marsh’s Scales of Justice (1955) or William P. McGivern’s Very Cold in May (1950). It also goes without saying that whilst Wodehouse’s characters fall in and out of love on a frequent basis, they do not resort to bumping off unwanted fiancées nor kill out of unrequited love.

Blackmail occurs in Wodehouse’s stories, but in contrast to crime fiction of the time, it is treated more light-heartedly, though perhaps Richard Hull’s My Own Murderer (1941) is a possible exception. With Wodehouse blackmail is invariably for a good cause and is not usually deployed to gain money. The most well-known and humorous example can be found in The Code of the Woosters, in which Jeeves reveals to his employer that Sir Roderick Spode runs a ladies’ lingerie shop. This is a piece of information Spode does not want publicly known, as he is the leader of the Black Shorts, (Wodehouse’s send up of fascism). Wooster never uses this knowledge to get money from Spode, but later on in the book Wooster is able to hint at the information in order to stop Spode from beating up Gussie Fink-Nottle.

Finally, as mentioned in a previous section that both Wodehouse’s stories and mystery novels of the era employed the trope of mistaken or false identities, and one way this may occur is if a character is impersonating another. This is another common situation and problem, but again it is an area of divergence. With Wodehouse it is always played for laughs such as in Piccadilly Jim (1917), where the eponymous character ends up doing several impersonations, including at one point of himself, to win a girl’s hand and marry her and in ‘Bingo and the Little Woman’ (1922) Wooster impersonates a romance novelist to help a friend get his allowance reinstated. In contrast impersonations in crime fiction of the time is decidedly more deadly, with quite literally a killer example occurring in Lord Edgware Dies (1933). Impersonations in crime fiction were vital for securing alibis and for obscuring the victim’s time of death.

So there you have it. I hope you have enjoyed reading some of my thoughts on the connections between the Wodehouse canon and the mystery fiction he was writing alongside. If you have reached this far, then well done! Although I imagine if you have read it all then it is probably about time for my 10th anniversary blog post. I’ll try not to make that one as long as this one!

[1] In a letter he wrote in the 1960s, Wodehouse once talked about having to give up on Balzac’s Pere Goriot. The reason he gave was that he could not ‘take the least interest in the characters.’ Yet interestingly he followed up this comment with this cry: ‘Give me Patricia Wentworth!’

[2] See W. A. S. Sarjeant’s article ‘P. G. Wodehouse as Reader of Crime Stories,’ which was published in The Mystery Fancier (Vol. 9 No. 5) September – October 1987. This article more extensively looks at the way crime fiction made its way into Wodehouse’s work.

[3] See The Code of the Woosters (1938) (Curtis Evans writes on this title here, and points out the fact that Wodehouse directly references a novel by E. R. Punshon.)

[4] See ‘Do Butlers Burgle Banks?’ (1968)

[5] See ‘The Crime Wave’ (1937).

[6] See ‘Aunt Agatha Takes the Count’ (1922) and ‘Jeeves and the Greasy Bird’ (1965). Con artists and scams appear in interwar crime stories too, such as ‘The Genuine Tabard by E. C. Bentley and G. D. H. and Margaret Coles’ Burglars in Bucks (1930).

[7] See The Code of the Woosters (1938) and Much Obliged, Jeeves (1971).

[8] See ‘The Adventure of the Dorset Squire’ (1937).

[9] It is hard not to see Wodehouse’s ability to create absurd situations mirrored in Cyril Hare’s ‘The Tragedy of Young Macintyre,’ when a barrister attempts to sue an elocutionist for ruining his speaking voice. A farce really does ensue!

[10] This club is mentioned in the short story ‘The Abominable History of the Man with Copper Fingers’, which can be found in the short story collection, Lord Peter Views the Body (1928).

[11] This club is mentioned in Whose Body? (1923).

[12] John at his blog Pretty Sinister has commented on this aspect of the book here.

[13] At his aunt’s behest Wooster is pushed into trying to steal a silver cow-creamer in The Code of the Woosters and in ‘Jeeves Makes an Omelette,’ (1958) he is tasked with stealing a painting so his aunt will have a story for her ladies’ magazine. Whilst in Aunts Aren’t Gentlemen (1974), Wooster’s aunt asks him to nobble a racehorse!

[14] The wrong place can even be up a tree, as Wooster is discovered in one late at night outside a girl’s school by a policeman. Wooster was endeavouring to provide a distraction to enable a friend’s cousin to get back inside without being detected, but Jeeves’ quick thinking prevents anything disastrous occurring. This can be found in ‘Jeeves and the Kid Clementine’ (1930), which is included in the collection, Very Good, Jeeves (1930).

[15] ‘Jeeves and the Hardboiled Egg’ (1917) probably contains one of the most imaginative solutions to a lack of money.

Thanks for putting into words something which I dimly suspected. The special appeal of writers from the Golden Age has been difficult for me to articulate. I’m just a member of the browsing herd of readers, not a real critic for whom I have a lot of respect, by the way. But the great draw that Mrs. Mitchell, Josephine Tey, and Dorothy Sayers have lies, I think., in the catholicity of the aspects of so many of their characters and plots. There’s not much in the way of baroque mannerisms or contorted outlooks required to appreciate the daily trials of a pig farmer or a staff member of a girls school or an overworked teaching nun. Their quotidian efforts to negotiate the day are sensed by pretty much all of us. And the humor that Wodehouse injected into that trial of Sisyphus helps us to identify with those characters in unspoken agreement. Thanks again for bringing so much to my enjoyment of reading these great works from what increasingly seems to have been better days (in illo tempore).

On Sat, Jun 27, 2020 at 6:50 AM crossexaminingcrime wrote:

> armchairreviewer posted: “Today, it has been five years since I first > began writing this blog. How much has changed! I almost feel embarrassed by > my early reviews. (Cue everyone searching to read how bad they were). To > date I have managed to rack up 1133 posts and 1191808 words. Y” >

LikeLiked by 1 person

Glad you enjoyed the post.

LikeLike

Big congratulations and big thanks—your blog has enriched my reading life immeasurably, by pointing me to many books and authors of the type I like!

Your Wodehouse essay is impressive and, as I’m very keen on Wodehouse myself, a terrific thing to see here.

I, too, have often encountered subtle as well as more obvious evidence of “Plum’s” influence on Golden Age detective fiction in my mystery reading. And just the other day, I read a Gladys Mitchell (one of her Timothy Herring series from the 1960s[?]) in which the protagonists playfully debate (and make bets on) which Hollywood film producer from the Wodehouse canon the actual film producer they’re scheduled to meet will most resemble!

Because PGW lived and worked for so long, and because the beloved Jeeves and Bertie novels (as opposed to short stories) didn’t begin until the 1930s, it’s easy to forget how prolific, popular, and presumably influential he already was by the 1910s. So I guess he was both a peer and a precursor, in a way, to the Golden Age giants.

And speaking of PGW’s crime subplots: Though I’ve been reading and re-reading Wodehouse for decades, it was only just this week that I realized I should check out Sam the Sudden, since I always enjoy the Dolly/Soapy/Chimp trio of comical crooks when they appear in the books that I’m already familiar with.

Wodehouse, of course, has some problematic attitudes, which of course is unsurprising in a writer from his generation. The Jeeves and Bertie books, though they’re generally my PGW favorites, do seem to show an especially misogynistic side of him, in a way, in that most of the important female characters—the ones Bertie likes as well as the ones he dreads—are portrayed in one way or another as overbearing, manipulative, and self-centered. (I guess Madeline B. is a notable exception; but of course she’s supposed to be dislikable regardless, because of her sentimentalism.) As I began to read more of the non-Bertie books, I was relieved to find that at least some female Wodehouse characters are potrayed in a way that I would consider more positive—bold and smart and self-actualized, but also kind to others.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Regarding the regrettably negative potrayals of women in the Bertie books: Perhaps a reason that things went in that direction in that series specifically was the “dramatic necessity” of surrounding Bertie with acquaintances who were always trying to manipulate him in one way or another, while also keeping the cast free of anyone who would be a genuine love interest for Bertie. Since Wodehouse largely (and expertly) populated his work from a menu of his “types,” and because he was so sharp and economical a writer, he might have felt that a smart/bold/self-actualized/kind female “type” would be superfluous to a Bertie story, as opposed to a Blandings or miscellaneous book where a likeable Sally or Pat could team up with other protagonists in a positive way. (Not to excuse the misogyny, of course, in any event.)

LikeLiked by 3 people

I haven’t read the Mitchell title you refer to, but one of the important things I learnt when researching this post, is that Wodehouse wrote for a really long time! I was finding myself surprised by the late publication dates. But I guess this is due to the fact that the stories/TV adaptation reinforce the 20s/30s setting.

I think your ideas for why Wodehouse had to avoid a self-actualised female are definitely plausible. Wooster after all, would not work as a character once he was married. Jeeves certainly wouldn’t approve! I guess the male characters in these books sort of get what they deserve, as they don’t pull the annoying female of the moment, up for their poor behaviour.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Yes, it always amazes me to reflect that Wodehouse was a published writer before my grandmothers were born; and yet, when he wrote his last book, I was already old enough to read it upon publication (though I didn’t)!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wodehouse and Conan Doyle (and Conan Doyle’s brother-in-law E. W. Hornung, creator of “Raffles, the amateur cracksman”), played cricket together on the Authors team captained by Doyle, not golf.

In the first part of “Thrones, Dominations” left unfinished by Dorothy L. Sayers (later completed by Jill Paton Walsh and published in 1998), Lord Peter Wimsey marries Harriet Vane and engages a lady’s maid for her, “accompanied by a whole library of manuals on etiquette and the complete works of Mr P. G. Wodehouse whom, not without justice, she took seriously as an infallible guide to high life above and below stairs.”

LikeLiked by 2 people

I never knew about the cricket link. Doyle certainly took quite an interest in sport. Thanks for sharing that snippet from TD. I read the book years ago, but I had completely forgotten about that bit. Very appropriate!

LikeLike

Great post on a great blog. Congratulations on the anniversary!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks!

LikeLike

I’m surorised you don’t mention the English farceur novelists, Michael Innes and Edmund Crispin, who aren’t influenced by Wodehouse just in their tone but also in their characterisation and plots.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Posted too soon!

Have you come across Jeeves: A Gentleman’s Personal Gentleman by C. Northcote Parkinson (of Parkinson’s Law fame)? It’s a biography of Jeeves, of course, and reveals he was the son of a First Wrangler who took to drink and married a barmaid. However, there’s an interesting encounter between the young Jeeves and Bunter where Bunter recommends Jeeves to find the most foolish employer he can, for his own comfort. Being employed by Wimsey is not a bed of roses, as Bunter can never relax; hence Jeeves’s selection of Bertie.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Although Jeeves does have to work hard to keep Bertie out of the consequences of his often stupid actions, so maybe the grass isn’t always greener on the other side.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have not come across the Parkinson book, but it sounds very intriguing, with its merging of fictional worlds.

LikeLike

It wasn’t a deliberate omission, they just didn’t spring to mind when I was thinking of examples. I read a lot of Crispin and Innes in my pre-blog days, so my memories are not quite so fresh, as they are with other authors. Which titles/scenes would you say are indicative of the Wodehouse influence?

LikeLike

Both of them share Wodehouse’s fondness for games with English literature; they have a taste for farcical situations; their plots have the complexity of Wodehouse’s, with things going awry because of other characters’ interventions.

With Crispin, I’d put forward The Moving Toyshop, with Innes, Appleby’s End or Hamlet, Revenge!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve read TMT by Crispin and I agree it has Wodehouse elements – the finale chase is definitely madcap enough to feature in a Wodehouse story!

LikeLike

1 Congratulations!

2 Interesting topic. I had never even thought of it.

3 Death of My Aunt by Kitchin fits the topic very well indeed.

4 You have no need to apologize for any review.

5 Except the Akunin reviews of course, for which no apology can suffice!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks. I have not managed to get a copy of that Kitchin novel. The only one I have read so far is his Christmas-time set one.

LikeLike

Good stuff. For a footnote to your crime studies you like like to read my Wodehousean blog post https://noelbushnell.wordpress.com/2018/07/14/cops-and-robbers-and-other-hairy-tales/ You can forget all the Wodehousean blather about beards at the start if you like and get down to the nitty gritty about burglary in the second half. Pip pip

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for the link Noel!

LikeLike

Congratulations on the first 5-years Kate. Murder in Common celebrates 7-years in the autumn and I too cringe at some of my earlier posts. It took awhile to find my voice and I sometimes wonder what my voice will be in the coming years.

Best..

June Lorraine

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Lorraine!

LikeLiked by 1 person

A scholarly work indeed! I am sorely tempted to re-blog it, if you would permit it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks! Yes I am happy for you to re-blog as along as the post origins, (author/name of this blog), are acknowledged.

LikeLiked by 1 person

But of course. Much obliged!

LikeLike

Congratulations, Kate! Your blog has become a must-read for me, and I’m sure for many others.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks Christine!

LikeLike

Reblogged this on ashokbhatia and commented:

The brainy coves amongst us often keep twiddling our thumbs trying to figure out if crime and humour go together in the realm of literature. Those who have waded through ‘Hot Water’ or many other whodunits dished out by P G Wodehouse would readily respond in the affirmative. Those who also happen to be fans of the likes of Agatha Christie and others would heartily approve of the sentiment, but may not be aware of the kind of impact our master story tellers have had on each other’s works.

Here is a scholarly piece (if piece is indeed the word I want) which goes deeper into the question of Plum’s influence on classic crime fiction.

LikeLike

[…] read with Rekha, the Christie Cover quiz made a return to the blog, I celebrated my blog’s 5 year anniversary last Saturday, and I also took part in the Top Ten Tuesday meme for the first […]

LikeLike

Congratulations on your anniversary, Kate. The years do fly by, don’t they? I have never read P.G. Wodehouse; you have inspired me to remedy that.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks! And his books are not that long. They’re very easy to read in one sitting, so he is definitely worth a go.

LikeLike

[…] I decided to just pick one title by Wodehouse for the list, but you can read more about my thoughts on his work and the genre of crime fiction here. […]

LikeLike

[…] P. G. Wodehouse’s Influence on Classic Crime Fiction by Cross Examining Crime (WordPress Blog) 27 June 2020 […]

LikeLike

Oooh, this is such a wonderful read- rubbing my hands in glee!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh thank Manav! Glad you enjoyed it!

LikeLike

Congrstulations, Kate. Well done and great post.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you!

LikeLike

Delightful post; I did think of and also come across some discussion on the connections between Wodehouse and Christie (including a letter from the former to the latter where he says about The Hollow. “The people in it simply gorge roast duck and soufflés and caramel cream and so on, besides having a butler, several parlourmaids, a kitchen maid and a cook. I must say it encouraged me to read The Hollow and to see that Agatha Christie was ignoring present conditions in England.) He was apparently encouraged by Christie as to his own country house settings.

Lord Peter is another who springs to mind but I hadn’t considered how wide his influence actually may have been

LikeLiked by 1 person

Glad you enjoyed the post and thank you for sharing that snippet about The Hollow.

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] This story was published in Nash’s in the UK in 1910, and in Burr McIntosh Monthly in the USA. This second version again was longer and it also had its setting changed to an American one. The tale revolves around James Buffin who is sent to prison after a policeman catches him sandbagging an individual who had crossed him. Buffin vows to has his revenge on the policeman who arrested him. However, this plan goes badly awry. I think Wodehouse was more comfortable at writing this type of crime story and as such the plot twists work better. I feel this narrative is a pre-cursor to the irony laden mystery fiction of Francis Iles and Richard Hull and is a good reminder of how influential Wodehouse was on other authors at that time – a topic I explored more fully in my 5th anniversary blog post. […]

LikeLike

[…] on my blog I have discussed the influence of P. G. Wodehouse on detective fiction, and today’s read contains more than a trace of Jeeves and Wooster. The […]

LikeLike

[…] a fun introduction to the series amateur sleuth, Boisjoly. This character parodies some elements of P. G. Wodehouse’s Bertie Wooster (school chum network with bizarre nicknames, the solving of domestic and […]

LikeLike

[…] he would change over time, as a character, Lord Peter Wimsey is launched in his debut case in the Bertie Wooster mould, (although he is arguably more knowledgeable and intellectual than Bertie). In a later […]

LikeLike

[…] He goes on to say that Rinehart’s ‘tales are unfailingly filled with sentimental love stories and gentle humor, both unusual elements of crime fiction in the early decades of the twentieth century.’ This is a statement I find it difficult to agree with given the numerous crime stories published at the time that refute it. Patricia Wentworth anyone? Gentle humour crops up a great deal in crime fiction of the era, due to many factors including the influence of P. G. Wodehouse’s work which showed that it could be highly effective to write a crime story comically. This is something I have explored more fully in a previous blog post. […]

LikeLike

[…] could picture them being in a P. G. Wodehouse novel and the thought that one of them is soon to become a vicar’s wife, might seem unlikely. Yet at […]

LikeLike