This is a book I have had my eye on for some time, but it took me a while before I managed to acquire it. Reasonably  priced copies have been fairly elusive. To date I have read 14 of Berkeley’s books and last November I even ranked 12 of them in a post.

priced copies have been fairly elusive. To date I have read 14 of Berkeley’s books and last November I even ranked 12 of them in a post.

Berkeley, according to Turnbull ‘has been called one of the important and influential of Golden Age writers by such authorities as Haycraft, Symons and Keating.’ I would also add at this point that JJ, writer of The Invisible Event blog, selected him as one of his Kings of Crime back in 2015. Turnbull continues: ‘Yet he occupies a surprisingly ambivalent position in the history of the crime genre. To enthusiasts, he has attained cult status, and ranks among the all-time greats; otherwise he is a little-known and unjustly underrated figure. Just a fraction of his considerable output has been reprinted in the years since his death […] and that only intermittently. The Poisoned Chocolates Case, Trial and Error, Malice Aforethought and Before the Fact are the only titles reissued with any frequency…’ I did pause at this point to consider how much or little things have changed in this respect. All four of titles Turnbull picks out are still the easiest works by Berkeley to get a hold of. Others by him have been reprinted since the publication of Turnbull’s book, but they too have sadly gone out of print. I don’t think he is as ‘little-known,’ though I still feel in part he remains an ‘underrated figure.’

A key positive of this book is the fact Turnball looks at the full range of writing Berkeley produced, considering his sketches, comic operas, fantasy fiction and political analyses, as well as his crime fiction and crime fiction reviewing output. I felt this was important as so very often Turnbull shows how Berkeley’s non-mystery fiction writing influenced his mystery novels. Moreover, his inverted mysteries, Malice Aforethought and Before the Fact, are commonly cited as his ‘major achievement,’ yet I was pleased that Turnbull reveals how many other novels written by Berkeley are full of merit. Though I was intrigued by the idea that Julian Symons felt that Berkeley’s novels under the Iles penname were great ‘influences on post-war detective realism in Britain.’

Turnbull’s book begins with a potted history of Berkeley, followed by a series of chapters which focus on and separate Berkeley’s work by his various pennames, with the Roger Sheringham titles getting a chapter of their own. Looking at Berkeley’s family history there are quite a few points of interest:

- His father interestingly became known for ‘pioneering [an] x ray machine, which he used for locating shrapnel in patients during’ WW1.

- On his mother’s side he is related to the 17th century Robert Carey, Earl of Monmouth and a house related to that family was called Platts. This was interesting because the penname he used for Cicely Disappears (1927) was A. Monmouth Platts.

- His mother’s maiden name was Iles, so that explains another penname of his.

- His family tree also included a botanist and smuggler and Berkeley is said to have enjoyed investigating his family tree later in life.

- Berkeley’s mother wrote a novel called The School of Life: A Study in the Discipline of Circumstance, a novel which had some parallels with her own life. Intriguingly there is a town named Sheringham in it, so I wonder if that is why Roger’s surname came from?

An idea which crops up in this book is that Roger Sheringham is a character who is said to voice some of Berkeley’s ‘own attitudes and opinions on British society between the wars’ and this is where Turnbull’s discussion of Berkeley’s political writings become so vital, so the two go hand in hand. Something I hadn’t heard of before was the idea that Ambrose Chitterwick was ‘more of a self-portrait.’ From the 30s onwards Berkeley is said to have become anti-government, though still pro-royal. A penalty for a motoring offence so riled Berkeley that he went on to write a short story around the theme, with a sting in its tail for the police. I was especially fascinated to hear how intensely keen Berkeley was to prevent Edward VIII from abdicating and marrying Mrs Simpson. He hired lawyers and private investigators to try and prove that Mrs Simpson’s divorce was not complete, and he was prepared to be a witness for the prosecution if it went to court. He went as far as creating a journal of activities and evidence, though he was not able to get it published.

One of the reasons I enjoyed the chapter looking at Berkeley’s sketches and skits for Punch and similar publications, was that often you would see the glimmer of a later novel. For example, Berkeley wrote a story called ‘The Sweets of Triumph,’ for Passing Show in 1924, which has a writer’s book sales shoot up after a box of chocolates is poisoned. Whilst another example which caught my eye was ‘The Right to Kill,’ which he wrote for the Democrat, involving an anaesthetist who hears a drugged patient talk about how he loves the anaesthetist’s wife, and I think he then thinks the patient has been having an affair with her. He is tempted to kill the man, but what does he do? Equally JJ will be thrilled to know that his favourite Berkeley title, Mr Priestley’s Problem (1927), was based on an unpublished short story called ‘Nothing Ever Happens.’ His magazine work in the 20s was also of great interest to me because his skits often parodied or joked about mystery fiction and some of his pieces include tongue in cheek how-to guides to writing a detective novel. One such piece, (I think), also included his formula for writing one:

‘First of all think of a murder (a sound jewel robbery, with plenty of titled names in it, will do at a pinch; but there’s nothing like a good juicy murder); then formulate a set of circumstances under which it could not possibly have been committed; surround the victim with several persons all of whom had an excellent motive for murdering him, but none of whom could possibly have done so; and go ahead.’

He even did a Holmes parody called ‘Holmes and the Dasher,’ which is written in the style of P. G. Wodehouse. A lot of this earlier work is included in Jugged Journalism (1925), which I have just bought a copy of, as I would love to read it for myself. If you too want a copy ignore the absurdly priced copies on Abe books and buy one of the two reasonably priced copies on Amazon, before they’re gone.

Having read most of the Sheringham novels I was quite interested to see what Turnbull had to say about this character. He emphasises the importance of Roger’s fallibility, and how he deviated from the norm at the time. Turnbull also includes this remark by Leroy Panek:

‘[Berkeley], I think, asked himself what kind of man would have the gall to push himself into other people’s private affairs, to intrude where he is not wanted, to assume the duties of others, the police, and to have sublime faith in his own perception and acumen. His answer was a very disagreeable one.’

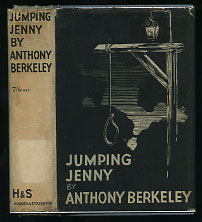

I felt this was a fascinating way of looking at Sheringham’s more unpleasant aspect. Roger’s reliance on the psychological approach to solving crimes is equally shown to be one of his stumbling blocks, as sometimes his psychological clues very much lead up the garden path straight into a dead end. Turnbull also picks up on the true crime cases which influenced many of Berkeley’s titles such as the Florence Maybrick Case, which inspired Berkeley’s The Wychford Poisoning Case (1926). Interestingly Berkeley felt this title was ‘fit only for incineration,’ whilst Dashiell Hammett felt the ending was ‘flabby’ and ‘unsporting.’ Working through Roger’s cases chronologically was very helpful for me, as my own reading of them has been fairly jumbled up in terms of reading order. As well as getting a mini biography of Roger, (gleaned from the books themselves and an intro Berkeley wrote for the American printing of Jumping Jenny), Turnbull does a good job at exploring the ‘nonconformity’ of the Sheringham titles, especially when it comes to the execution of justice. I never realised how few entries have the police apprehend the killer. I also agree with Turnbull that ‘the multiple solution and compound surprise ending are distinctive, readily identifiable characteristics of most of Anthony Berkeley Cox’s crime writing…’

psychological clues very much lead up the garden path straight into a dead end. Turnbull also picks up on the true crime cases which influenced many of Berkeley’s titles such as the Florence Maybrick Case, which inspired Berkeley’s The Wychford Poisoning Case (1926). Interestingly Berkeley felt this title was ‘fit only for incineration,’ whilst Dashiell Hammett felt the ending was ‘flabby’ and ‘unsporting.’ Working through Roger’s cases chronologically was very helpful for me, as my own reading of them has been fairly jumbled up in terms of reading order. As well as getting a mini biography of Roger, (gleaned from the books themselves and an intro Berkeley wrote for the American printing of Jumping Jenny), Turnbull does a good job at exploring the ‘nonconformity’ of the Sheringham titles, especially when it comes to the execution of justice. I never realised how few entries have the police apprehend the killer. I also agree with Turnbull that ‘the multiple solution and compound surprise ending are distinctive, readily identifiable characteristics of most of Anthony Berkeley Cox’s crime writing…’

I appreciated Turnbull giving Chief Inspector Moresby and Ambrose Chitterwick a separate chapter mostly to themselves. For one thing it gave me a greater understanding of Moresby’s role in the Sheringham tales and how he is designed to detect in an opposing manner to Roger, relying on physical clues and routine police legwork. Although he is not above a spot of psychological manipulation if he wants Roger to do something. Discussion also  turns to Chitterwick and other characters who could be described as ‘self-effacing and deceptively insignificant little men,’ which turn up quite a few times in Berkeley’s stories, and not always on the side of good. Turnbull also includes various quotes from other writers who have commented on Berkeley’s work and I think he uses these quotes very effectively. I was quite drawn to this idea from Strickland that Trial and Error ‘is a mad tea-party of a book, with the inverted form combined with the puzzle, the courtroom drama with near farce, the novel of suspense with the comedy of P. G. Wodehouse.’ Yet, I think Barzun and Taylor might be over reaching themselves in suggesting that Murder in the Basement anticipates the police procedural subgenre by many years.’ But maybe that is just me? In this chapter and others Turnbull also refers to the radio and play scripts that Berkeley wrote as well as the collaborative writing projects that he took part in.

turns to Chitterwick and other characters who could be described as ‘self-effacing and deceptively insignificant little men,’ which turn up quite a few times in Berkeley’s stories, and not always on the side of good. Turnbull also includes various quotes from other writers who have commented on Berkeley’s work and I think he uses these quotes very effectively. I was quite drawn to this idea from Strickland that Trial and Error ‘is a mad tea-party of a book, with the inverted form combined with the puzzle, the courtroom drama with near farce, the novel of suspense with the comedy of P. G. Wodehouse.’ Yet, I think Barzun and Taylor might be over reaching themselves in suggesting that Murder in the Basement anticipates the police procedural subgenre by many years.’ But maybe that is just me? In this chapter and others Turnbull also refers to the radio and play scripts that Berkeley wrote as well as the collaborative writing projects that he took part in.

When moving on to discuss Berkeley’s writing under the Francis Iles penname, Turnbull includes this remark Berkeley made on authors needing to separate their disparate works:

‘The reading public demands consistency in its authors […] If Mr X, who has specialised in cosy suburbanism, gets an urge to write a stream of consciousness novel about a Siberian bird-watcher on Lake Chad, he must either suppress the impulse or unburden himself under another name.’

True crime also seems to have been a heavy influence with Malice Aforethought and Before the Fact, as the former bears a number of parallels with Major Herbert Rowse Armstrong’s murder of his wife in 1922 and Johnnie Aysgarth, who appears in the latter is ‘based on the notorious mass poisoner William Palmer.’ Whilst, As for the Woman, the third Iles novel, is said to have been ‘inspired by two celebrated murder trials, the Thompson-Bywaters and Rattenbury-Stoner cases.’ Various critical viewpoints are included for these texts and we even have Berkeley’s own thoughts at times, as for instance it seems he had qualms over how effectively he had rendered Lina’s motivations for what she does and doesn’t do, in Before the Fact.

One of the things I enjoyed about the chapter which explores Berkeley’s nonfiction work is that we get to see which crime writers he did and didn’t enjoy. Like fellow crime fiction reviewer, Dorothy L. Sayers, he too wanted authors to write in good English. Agatha Christie, Sayers, Ngaio Marsh and Georgette Heyer, were all big-name authors that he enjoyed, but he also praised works by Belton Cobb, George Bellairs and Christianna Brand. He wasn’t keen on Margery Allingham’s work and felt Gladys Mitchell’s to be uneven. I think if Berkeley was reviewing crime novels today, he would not be pleased with the focus the detective’s personal life now gets, as at the time he wrote: ‘that some writers’ fashionable propensity for describing the purely personal problems of their detectives tended to detract from the main interest of their novels.’ Moreover, despite being a writer who provided many a novel with a shocking ending, he once wrote that:

‘It is the ending which is the Achilles’ heel of crime writing. So many otherwise good books are ruined by pandering to the convention which decrees a shock of some sort in the last few pages.’

However, I feel he does have a point, as only this month in a review for an Elisabeth Sanxay Holding title, I wrote that ‘a shock in and of itself does not guarantee a pleasing end and in fact needs to be carefully built up to.’

Berkeley was not a huge fan of crime fiction from the US either, opining that:

‘The Americans never seem to do things by halves… Quite nine-tenths of American thrillers, and even detective novels, fall slap into one of two categories: the tough or the sentimental… And when they are tough they are very very tough, and when they are sentimental they are slushy.’

He disliked the hardboiled subgenre and Ellery Queen, the character, describing him as ‘a pompous windbag who never uses five words when fifty will do.’ However, some American writer he did like were: Erle Stanley Gardner, Emma Lathen, Patricia Highsmith, Margaret Millar, Rex Stout, Stanley Ellin, Evelyn Berckman, (who I am going to review next,) and Lilian Jackson Braun’s cat detective Koko. I was a little surprised by this last one. I did not see him as a fan of a cat who detects.

He expected high standards of reviewers and did not approve of reviewers praising friends’ work simply because they were friends and even worse not criticising their works despite their being worthy reasons for doing so. So important was this matter to him that Berkeley wrote a satirical letter to Time and Tide about it, bemoaning how he is the only reviewer who doesn’t get bribed by authors. Tongue in cheek he wonders where he has gone wrong…

We then arrive at the conclusion and I think Turnbull does a good job of rounding things up. He considers why so many of Berkeley’s books are over looked. Is because they ‘date badly’? Is it because of his prose style which is sometimes ‘elephantine, awkward and dull,’ as Panek suggests? There is also the query of whether it is because ‘most of his stories followed the same basic plot pattern.’ This is not an idea I had really considered before. I’ve always found Berkeley’s novels to be quite varying, but I would be interested to know what others think. The criticism of there being a ‘lack of engaging and sympathetic characters’ is one I am not surprised by, though Turnbull does explore this issue from more than one point of view. Turnbull also looks at the achievements of Berkeley’s work such as how they reflect life more, in the way the investigators don’t get the answer first time and the fact that the clues have more than one interpretation. There is also Berkeley’s ‘redefinition of murder’ and the way that his books frequently work with the theme of justifiable murder.

Elusion Aforethought is great for reminding you of the richness of Berkeley’s work and is written without rose tinted spectacles. Turnbull’s prose style is engaging to read and is not too dense. There are some contextual points for the era which are a little worn, but this is not too big an issue. I would advise reading this book when you’ve read most of the Berkeley’s crime novels as some spoilers are included, though not for every book. This is a compact work, but it contains a wealth of interesting and little-known information on Berkeley and the full range of his work. It is definitely one I would recommend this book to fans of Berkeley and of the golden age detective fiction genre.

Rating: 4.25/5

This book has been in one of the three TBR piles on my living room floor for a few months. Your enthusiastic review is an effective inducement for me to move it towards the top. I knew the book was rather slender, and it is great to hear that it is nevertheless wide-ranging in a thoughtful manner.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I actually enjoyed it not being on the large side, as it can be a bit off putting to work through much bigger tomes. I look forward to hearing your thoughts on it when it makes it way off your TBR pile. Why do you have three TBR piles, if I might ask? Are they thematic ones?

LikeLiked by 1 person

The number three referred to three physical piles. If I stacked everything into a single pile, I am afraid it would be about two meters high and would keel over with near certainty.

The piles indeed vary in theme, with one being mostly non-fiction or critical studies, another being mostly fiction I own, and the third being fiction borrowed from libraries (with interlibrary loans, if any, at the very top since they typically have the shortest turnaround time).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ah I do envy GAD fans who have library with great interlibrary loan facilities. My local library has about two classic crime novels in at any time and they are always reprints I have read. I guess I make up for it by buying lots of ex-library copies online.

LikeLiked by 1 person

A single pile is impractical for anyone that has cats, as there is no way a solitary tower of books isn’t going to get rubbed against. I myself have a bunch of separate stacks, all clustered together into a monstrosity that consumes a good portion of my desk.

– My dwindling stack of John Dickson Carr books. I actually keep this as two stacks, just because I once had that many Carr books to read. The tail end of this is the short story collections.

– A random assortment of authors that I’ve decided I want to read soon – Henry Wade, Frederic Brown, Peter Dickinson, Paul Gallico, etc. You’re probably responsible for half of this stack.

– My “early Christie” pile, which is for the first decade of her work that I’m reading in order.

– My “Christie I want to read” pile, which is an assortment of Christie books that I’ve decided I want to read soon for some reason or another. This currently houses such titles as There is a Tide, The Boomerang Clue, Peril at End House, and Easy Kill. A lot of these books are vintage editions and I probably just like the covers.

– My “modern Christie editions” pile, which is a stack of 70s/80s/90s editions that I’ve snatched from my parent’s house. This has a lot of books that I’ve heard are good, but I’d prefer to track down a $4 vintage copy before I actually read them.

– A pile of books by modern publishers like Ramble House and Rue Morgue. This gets its own pile just because these books have a larger form factor and don’t stack well with smaller paperbacks. That’s only partially true though, because for some reason these larger books are stacked on top of five Philip MacDonald books… Oh, dear…

– A stack of really big books, such as the Roger Scarletts. Again, this is just for stackability.

– A stack of British Library Crime Classics

– A somewhat random stack of Herbert Brean, Pat McGerr, Clayton Rawson, Anthony Boucher, and Craig Rice titles. I don’t really know why I have this stack. I guess these books were “recently acquired” at some point, and they have really nice covers that I wanted to look at, and so I stacked them closest to my computer, and there they sit…

Yeesh – I haven’t even gotten to the piles on the floor yet…. Back away. Back away.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Wow that is quite a collection of piles! I imagine the RMP and RH titles would make good base books due to their size.

I just have the one pile of books. Reaches 3/4s of the way up my leg, so not quite at toppling stage yet, despite my cat rubbing up against it. I try to space authors who I have more than one book of evenly through the pile. I try to make that new books don’t hog the top of the pile and wait their turn. I frequently change the order around depending on my mood of what I want to read and also what I need to read, if I’m doing a post on something. If I had them on a shelf I might categorise them a bit more, but at the moment lots of small piles of books wouldn’t be very convenient.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh and I am sure that Bev could give you a run for your money when it comes to who has the most TBR books.

LikeLike

It’s funny, because for all of my piles, I rarely tend to take a book off the top anymore – that only really applies to the Carr and first decade Christie piles. Most of my reading lately has been on a whim. I guess that’s one of the joys of finishing a book – wandering into my office and glancing around to see what I should read next. That’s fairly different then what I was doing a few years ago, where I maintained my pile order religiously.

LikeLike

I’ve seen this book around, but figured I wouldn’t buy it until I’d read most of Berkeley (at which point I’m sure it will be impossible to get my hands on). It looks like a really interesting read and maybe I shouldn’t be passing it up.

There are so many little nuggets in your review that I’m not even going to remember to comment on a fraction of them.

– It’s funny how Berkeley got involved in Edward VIII’s affairs, since that’s remarkably close to what Mrs Stratton is frowned upon doing in Jumping Jenny. It also somewhat contradicts the quote you included about pushing one’s self into others affairs.

– I have the US edition of Jumping Jenny with the biography of Sheringham that you mentioned.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well Berkeley was fairly contradictory. I have no idea why he was so keen to keep Edward away from Mrs Simpson, given his much more flexible viewpoint on relationships. Given the structure of the book you can easily hop over books you have not read, as Turnbull works chronologically where possible. The end of the book also has a synopsis for each of his published works, which I found very helpful. If you see a cheap copy it be worth getting now and saving until a little bit later. Prices for the book do fluctuate.

LikeLike

Excellent review of Turnbull’s book, which I highly recommend to all Berkeley enthusiasts—though I agree, better to wait until you’ve read most of his books before reading it. (One reason it’s slender is that Berkeley wrote books only between 1925 and 1939, and didn’t even start contributing to magazines until late 1922.) I also enjoyed the discussion of TBR piles, especially regarding cats. Berkeley was unhappy with what he considered England’s antiquated divorce laws (he had personal experience–his two marriages didn’t last long) and railed against them at (rather tedious) length in his 1934 book O ENGLAND (which I recommend to completists only). But if I remember correctly, he tried to use the laws he deplored to prevent Mrs. Simpson’s getting a divorce and marrying Edward VIII. I read his journal many years ago (in the Royal Archives—another item only for obsessive completists, which I clearly am). He didn’t seem to mind Edward having an affair with Mrs. Simpson, but was concerned that if he married her it might lead to the end of the monarchy, whether or not he abdicated (he even expressed concern in his journal that if Mrs. Simpson had children they might not be Edward’s and the throne would go to—gasp!–an outsider). It’s been years since I researched this so I may not have the details right, but I think that was the gist of it.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Yes it does like a very odd obsession for Berkeley to develop.

LikeLike

[…] many names Anthony Berkeley wrote under and I first heard about this title last week when I read Elusion Aforethought: The Life and Writing of Anthony Berkeley Cox (1996). So, I am quite impressed that in less than a week I managed to not only get a copy of Jugged […]

LikeLike

[…] been indulging in my interest with the work of Anthony Berkeley, reading Malcolm J. Turnbull’s overview of Berkeley’s life and works, as well as having a laugh out loud read with Jugged Journalism, (a […]

LikeLike

[…] Elusion Aforethought: The Life and Writing of Anthony Berkeley Cox (1996) by Malcolm J. Turnbull by Kate Jackson […]

LikeLike

[…] I read in Elusion Aforethought: The Life and Writing of Anthony Berkeley Cox (1996) by Malcolm J. Turnbull, that Berkeley gets his own back a little in this story. American […]

LikeLike

[…] Elusion Aforethought: The Life and Writing of Anthony Berkeley Cox has been reviewed by Kate Jackson at Cross-examining Crime. […]

LikeLike