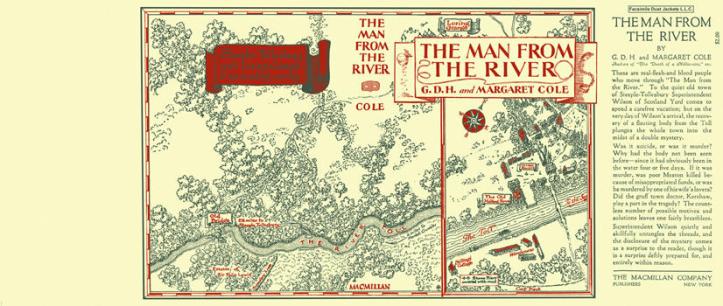

Vintage Mystery Scavenger Hunt Item: Map

I have never read a full length Cole novel, though I did experience their work in the Detection Club’s collaborative novel, The Floating Admiral (1931).This story begins with Harley Street consultant Michael Prendergast taking some time off in the sleepy town of Steeple Tollesbury. Unfortunately having initially desired peace and quiet, after only a few days he is bored and wants the company of friends. A quick ring round leads to Superintendent Henry Wilson coming to visit him. A friend he did expect to come but couldn’t, was Mark Warden, who having retired from cricket has become a junior partner in a stock brokering firm which his father, Nicholas Hanborough and William Meston built up. This may seem like a tangent but all is not well at the firm and Meston, who is staying at the same inn as Prendergast has something on his mind. Then one night, leaving his luggage behind, he disappears.

The mystery is soon solved though when a few days later Meston’s body is dragged out of the river, having by snagged by a tugboat. Police, locals and visitors alike are keen to decide whether it is suicide, accident or murder. Prendergast is of the conviction he was murdered, having quickly ascertained that he died of a broken neck. However the local police surgeon has much chagrin towards him, disliking Prendergast’s presence immensely. He conversely believes it must have been an accident or suicide. After all his wife had left him, frequently being seen in the company of other men and wanted a divorce. Prendergast is suspicious of the police surgeon to say the least, which seems well founded when the Chief of County Police, Colonel Lockwood tells Prendergast that Meston’s death was accidental due to a contusion on his head found at his post-mortem. Yet Prendergast knows when he examined the body there wasn’t a contusion there. So what is going on?

Thankfully Prendergast’s friend Wilson arrives and not a moment too soon, as the case surrounding Meston’s death is a complex one. It seems at Meston’s place of work embezzlement has been occurring. Was he the embezzler or did the real embezzler silence him? There is also the possibility that either Meston’s wife or one of her ardent admirers did the guilty deed, a possibility heightened by a blast from the past. Further suspects are to follow with more than one local person acting suspiciously, so it will take all of Wilson’s detecting acumen to solve this case – dogged by the local busybody, a retired solicitor, each step of the way of course.

Overall Thoughts

Initially I thought the Coles’ were going to be adept at characterisation as they seemed good at conveying human foibles, such as when people are stuck with others who bore them on holiday and whom they can’t shift and therefore have to avoid. However, for me I didn’t feel there was much depth to the characters. Granted the Wilson and Prendergast dynamic has its’ funny moments, with Wilson never taking Prendergast seriously and out of all the characters Prendergast is the one we get to know the most. Yet conversely Wilson is a bit of a puzzle. He is the central sleuth and is composed of a variety of fictional sleuth traits, but he doesn’t have any of them particularly strongly. Moreover, Sylvia Meston is set up as an interesting figure. By characters such as Michael she is castigated for being a ‘predator’ and a ‘Minx.’ She is described as ‘the sinner.’ But what makes her interesting is that she is aware of her faults but dislikes being stereotyped by them or being prevented from acting outside of them. But, although she is described as an ‘obvious siren,’ which makes her feature a lot in the potential motives of the suspects, I think the characterisation surrounding her is insufficient to make this a very convincing possibility. In general I would say that not enough time is spent with some of the main players in the tale, which marred the execution of the solution (in terms of killer choice and motivation), as the characterisation was not impactful enough to make it as plausible and realistic as it should be.

I did wonder whether the prose would have a socio-political stance to it, given the socialist leanings of the Coles. Yet I didn’t really get much glimpse of this. A group of characters who live at or visit the Grange regularly, arguably represent the capitalist irresponsible and party loving bright young (ish) things (a milieu recreated famously in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby). There is a slight reminder of P. G. Wodehouse’s Jeeves and Wooster but it is fleeting and lacks the humour. This group of people are not consistently criticised by the narration for their way of life, though some comment is made on how the Lorings can afford to maintain the Grange:

‘Oh that’s Tulumba… Rubber, I mean. You know Father and Godfrey both get disgustingly rich on rubber plantations. So Godfrey can afford to have the place properly kept up… We couldn’t do it if we weren’t bloodsucking capitalists. But it’s rather nice, isn’t it?’

Enda Loring is very candid about who they are here and it also comes out that during WW1 they didn’t have to plough up their park because Enda’s father ‘was on the County Agricultural Committee,’ which hints at class bias. When the narration focuses the most on the people at the Grange it is to undercut the fun notions a carefree well to do lifestyle usually has: ‘So far from being a giddy haunt of vice, Loring Grange appeared at the moment to be nearly the most boring place on earth.’ Additionally this is probably my own wrong error, but I did assume that considering the Coles’ background they might have included more realistic and balanced depictions of working class characters. However, this does not seem to be the case in this story. The ending was also very unsettling and not what I would have expected of the Coles (again probably another wrong assumption on my part). But its’ sense of morality is certainly skewwhiff and nearly falls into the naïve territory of the fairy tale.

Overall I felt that the Coles’ writing style was not very thematic. The text meaning stays very literal and it’s not because of its sparseness, as Christie’s writing style was not dense, yet today we are still discussing and debating the meaning of her work. The Coles’ writing style is not dense and it’s not very dull. But it doesn’t grip you either and I think it lacks life. Wilson’s approach to policing is a little like Inspector French’s, in its’ exactitude, though he is not above a spot of burglary. The final solution in terms of its mechanics was intriguing and unusual – though I still wonder how it could have been done without making a racket. Although my rating for this book is a little low, I don’t think I have given up on the Coles. I just don’t think I have found their best book yet. This one did have promise in terms of the maze they created with their crimes and characters, interlinking and mudding the investigative waters. I just think they needed to improve on their character depth and to add a bit more life into their prose.

If you have a favourite Cole novel let me know as I am keen to give them another go.

Rating: 3.5/5

[…] Source: The Man from the River (1928) by G. D. H. and Margaret Cole […]

LikeLike

DEAD MAN’s WATCH is really very good. I also liked BURGLARS IN BUCKS. Both of these have a witty sense of humor and sort of make fun of a lot of the genre’s plot motifs. For years I thought their books were meant to be parodies of the genre. Then I came across the Mrs. Warrinder stories (many of them not very good at all) and that changed my opinion of their writing style and intent. I attempted to read the Haycraft-Queen cornerstone book THE BROOKLYN MURDES for the first time early this year and made it to almost the halfway point before I gave up. This one is written solely by Douglas Cole with the help of his wife. It just goes on and on and on. It’s nearly 400 pages long in my edition! Is it the first epic length detective novel of the 1920s? Certainly felt that way. It’s very innovative in that it tells the story of two murders which seem unrelated but then it is slowly revealed that one man may have killed the other. It’s filled with incidents and clues and red herrings that complicate the mystery but it just seemed they were hindering the story rather than advancing it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for the suggestions. I’ll try to look out for them. Humorous crime fiction is usually up my street. The Coles are good at creating plot complexity in terms of the mystery but there was something missing from the writing style and investigation for me in this one. 400 pages is quite long for a 1920s crime novel – can’t think of any others off hand.

LikeLike

Oops! I meant to writer BROOKLYN MURDERS was written *without* the help of Cole’s wife. But I did use the word “solely” up there and you probably wondered why. :^) I type so fast sometimes that my fingers just don’t do what my brain tells them to do.

Curt wrote about MAN FROM THE RIVER on his blog and he says that it was primarily written by Douglas Cole even though his wife gets credit on the cover and title page. My experience is that the books where they are true collaborators is that the humor comes out more. So maybe this was her contribution. I have yet to read Curt’s book he refers to below. I’m sure he goes into this in detail.

LikeLiked by 1 person

ah mystery solved!

LikeLike

There’s a lot of analysis of the Coles’ detective fiction in my book The Spectrum of English Murder, which gets to a lot of the questions you raised as well as recommends titles. Brooklyn Murders was written by Douglas Cole, as was The Man from the River, which I reviewed on my blog.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh was Margaret not involved in this book then?

LikeLike

[…] The Man from the River by G. H. D. and Margaret Cole (Item: Map or Chart) […]

LikeLike