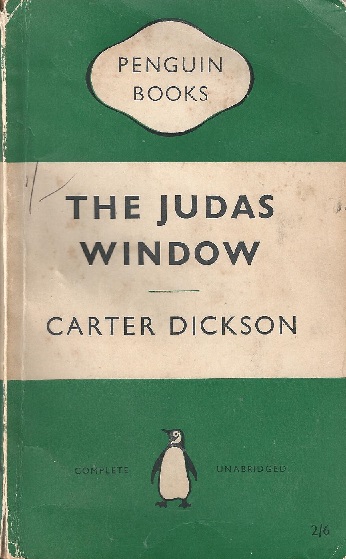

Aside from this being one of John Dickson Carr’s (writing as Carter Dickson), most famous and most revered novels, I am also reading The Judas Window (1938), as part of The 1938 Club challenge which is being run this week at the blog, stuckinabook. The novel begins in an eerie fairy tale romance manner, with Jimmy Answell having a whirlwind romance with Mary Hume, which leads to their engagement. In due course Answell goes to meet his prospective father in law, Avery Hume at 12 Grosvenor Street (where his butler Dyer, his brother Dr Spencer Hume and his housekeeper Amelia Jordan also reside.) The narrator is keen for us to identify with Answell, a man after our own hearts after all, being a fellow fan of murder mysteries. But because we know this is also a murder mystery we know something has to go wrong soon. Mary is anxious before Answell goes to meet her father, something Answell is feeling too. He tries to reassure himself thinking that ‘for anyone to be ill at ease about meeting the bride’s family, especially in this day and age, came to the edge of comedy.’ Yet a sense of foreboding is thrust into our face when the narrator responds to Answell’s pep talk, ‘It was not comedy.’ Answell enters Avery’s office/ strong room, with its steel window shutters already closed. On the wall are three arrows shaped into a triangle, which Avery won in an archery competition. Everything seems to be going fine until Answell drinks the whisky given to him, remembering nothing until he regains consciousness 20 minutes later, only to find Avery murdered on the floor, an arrow protruding from his chest. But with the room having been bolted on the inside and with seemingly no other points of access, who else but Answell could have committed such a crime? For the police it is a foregone conclusion, especially since his finger prints are on the arrow and it seems medical experts refute the idea Answell was drugged. As Answell comes up for trial there is only one man who can get to the bottom of this mystery and that is Sir Henry Merrivale…

Aside from this being one of John Dickson Carr’s (writing as Carter Dickson), most famous and most revered novels, I am also reading The Judas Window (1938), as part of The 1938 Club challenge which is being run this week at the blog, stuckinabook. The novel begins in an eerie fairy tale romance manner, with Jimmy Answell having a whirlwind romance with Mary Hume, which leads to their engagement. In due course Answell goes to meet his prospective father in law, Avery Hume at 12 Grosvenor Street (where his butler Dyer, his brother Dr Spencer Hume and his housekeeper Amelia Jordan also reside.) The narrator is keen for us to identify with Answell, a man after our own hearts after all, being a fellow fan of murder mysteries. But because we know this is also a murder mystery we know something has to go wrong soon. Mary is anxious before Answell goes to meet her father, something Answell is feeling too. He tries to reassure himself thinking that ‘for anyone to be ill at ease about meeting the bride’s family, especially in this day and age, came to the edge of comedy.’ Yet a sense of foreboding is thrust into our face when the narrator responds to Answell’s pep talk, ‘It was not comedy.’ Answell enters Avery’s office/ strong room, with its steel window shutters already closed. On the wall are three arrows shaped into a triangle, which Avery won in an archery competition. Everything seems to be going fine until Answell drinks the whisky given to him, remembering nothing until he regains consciousness 20 minutes later, only to find Avery murdered on the floor, an arrow protruding from his chest. But with the room having been bolted on the inside and with seemingly no other points of access, who else but Answell could have committed such a crime? For the police it is a foregone conclusion, especially since his finger prints are on the arrow and it seems medical experts refute the idea Answell was drugged. As Answell comes up for trial there is only one man who can get to the bottom of this mystery and that is Sir Henry Merrivale…

In the last novel I read featuring Merrivale, The White Priory Murders (1934), Merrivale blotted his copy book with me, coming across as quite an unpleasant and creepy person. But fortunately this is not the case in this novel where Merrivale cuts a humorous figure inside the courtroom, with his secretary Lollipop (one of the most ridiculous names I have come across in GA mystery fiction) helping him to control his more wilder verbal outbursts. The trial is seen through the eyes of Ken and Evelyn Blake, friends of Merrivale and in a way their discussions remind me of people commenting on a football match and I found this style effective as it humanised the events the reader sees. They are also characters the reader can identify with as they often react or express ideas and thoughts similar to those of the reader. Like us they are also wondering why the case was ever even taken to court. Why couldn’t Merrivale just solve the case pre-trial, like he has done so many times before? And what will his line of defence be? Into this Carr unsurprisingly enters the bizarre with Merrivale’s defence circling around a random collection of objects; an ink pad, a golf suit, for example. Moreover, early on Merrivale says the heart of the mystery is the Judas window. But like the Ken and Evelyn I could not fathom what he means by this until he reveals the solution at the end.

Something I particularly enjoyed about this courtroom based novel is that until the end it is by no means certain whether Answell is either definitely innocent or guilty, as the evidence brought forward is often ambiguous in that it can be read more than one way. So in a way it contrasts with other mysteries which significantly feature a trial such as Francis Iles Malice Aforethought (1931) and Alan Melville’s Warning to Critics (1936), where the reader is much more certain about the protagonist’s culpability. Moreover, just when you think Merrivale has got the prosecution on the run, they are quickly able to undermine the assuredness of his evidence during cross examination. This is an arena where Merrivale’s words and theories are not just taken for granted, which made for an interesting change. But what comes out through Merrivale’s defence certainly indicates there is more going on in this case than meets the eye. An impoverished cousin, a note of chivalry, a streak of family insanity and an absconding witness all add drama and suspense to this mystery. Merrivale definitely has his work cut out for him in this case, with there being a seemingly impressive mountain of circumstantial evidence against Answell and there is a reoccurring fear on the Blakes’ and readers’ part that Merrivale isn’t quite so sure of himself, with his success in court not just relying on his own brains but on the risky element of witnesses, who often seem to have agendas of their own.

Carr has constructed and written this novel exceptionally well with the tension rising and falling effectively. Merrivale’s solution to the mystery is an impressive and remarkable one and I think readers will be satisfied with how justice is served in this novel. Although this is not a comic crime novel there are veins of humour running through it, mainly in regards to Merrivale who is incongruous to his legal surroundings, but also in the way law and order is depicted as very early on in the story Ken creates an air of irreverence when he likens the law court to a school room. I had been worried that the narrative might become a bit dry or bogged down in details due to Carr’s usual focus on the mechanics of the impossible/ locked room crimes he creates. But in this I was thankfully wrong as Carr’s narrative style is engaging and also reveals a lot about the characters, even minor ones, through their experiences in the witness stand. This is definitely a Carr novel I would recommend for readers who love a tantalising puzzle but also for those who like drama and suspense, with well penned characters.

Rating: 4.5/5

See also:

I’m glad you enjoyed this one, Kate. It definitely made me feel bad for ignoring Sir Henry in my youth! The scenes in court are priceless.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes I’m still wondering what was written on the paper Lollipop shows Merrivale when he is about to have a verbal outburst in court…

LikeLike

I regard this as the best Merrivale. A tour de force.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well it is certainly my favourite Merrivale novel to date and I think it would be hard to beat.

LikeLike

[…] Carter Dickson – The Judas Window Crossexamining Crime […]

LikeLike

I do really like this one, but I’m not such as fan of it as most people seem to be. The revelation about halfway through of why Hume seemed to take against Answell overnight without any particular reason is, in my eyes, far better than the impossibility, and the final note of Merrivale’s revelation leaves a bit of a sour taste…but again most people seem happier with it overall.

For Merrivales, I rate The Plague Court Murders, She Died a Lady, The Peacock Feather Murders and probably a few others above this, but there’s certianly a lot of fun to be had from it and it’s among the upper tier of that character’s outings.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Always nice to hear from you JJ, I hope your hand is healing well. I think one factor which caused me to like this one a lot was that I had a poorer previous Merrivale read, The White Priory Murders, so Merrivale came across a lot better for me in this novel. I think I also enjoyed the tension created by the court room set up and Carr does do a good job at characterisation. I remembered really enjoying She Died a Lady, but then again that’s all I can remember about it. It has been a while though.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Having heard so mch about H.M. in court from the previous books in this series, it is nice to see him in his element…something of a wonder that Carr never returned him there at any future point (to my knowledge at least); maybe the old rapscallion blotted his copybook too heavily herein…!

The Hand is healing, thank-you. Starting up da blog again in a couple of weeks (though you’ve all coped perfectly well without me…), but got a post up in the next few days, too, sort of in preparatory throat-clearing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Glad you are on the mend and your posts are definitely missed, my Wednesday mornings just haven’t been the same. But I’ll look forward to your upcoming post.

LikeLike

[…] first is a classic Golden Age Detective novel called The Judas Window (1938) by Carter Dickson and I think this is a first rate court room based mystery where the reader […]

LikeLike

[…] in Christie’s Third Girl (1966) and A Caribbean Mystery (1964) and also in Carter Dickson’s The Judas Window (1938). Including this in a story can help to vary a plot and I also think it adds an additional […]

LikeLike

[…] The Judas Window (1938) by Carter Dickson […]

LikeLike

[…] Today is John Dickson Carr’s 110th birthday and JJ at The Invisible Event, who has a passing interest (and by that we read fanatical devotion) in Carr, decided to commemorate the occasion by exhorting fellow bloggers to contribute posts about the man and his work, which he is going to gather up into a summing-up post later today, as well as contributing his own pearls of wisdom. Not being quite so keen on Carr as JJ is (but then who is?), it has been a while since I last read any of his work, though if I had to pick my favourite three reads off the top of my head I would go for The Case of the Constant Suicides (1941), The Emperor’s Snuffbox (1942) and The Judas Window (1938). […]

LikeLike

[…] The Judas Window (1938) by Carter Dickson, […]

LikeLike

[…] captured by it in the way I have with other Carr novels such as The Case of the Constant Suicides, The Judas Window, The Emperor’s Snuffbox and Till Death Do Us Part. I’m not sure if my final rating is a little […]

LikeLike

[…] The Judas Window (1938) by Carter […]

LikeLike

[…] Search of the Classic Mystery Novel, Clothes in Books, ‘Do You Write Under Your Own Name?’, Cross-Examining Crime, Vintage Pop Fictions, The Green Capsule, Classic Mysteries, and The Grandest Game in the […]

LikeLike

[…] 5. Carter Dickson: The Judas Window (April 27). David Horne appears as Sir Henry […]

LikeLike

[…] No. 6: The Judas Window (1938) by John Dickson […]

LikeLike

[…] John Dickson Carr/Carter Dickson (Added to Haycraft’s inclusion of The Crooked Hinge (1938) and The Judas Window (1938). Seems an odd addition as it overlooks classics such as Till Death Do Us Part (1944), She […]

LikeLike