Right well I hope everyone has had a good night’s sleep and that you are bright eyed and bushy tailed for part 2 of my dissection of  Jessica Mann’s Deadlier than the Male. If you haven’t had the chance to read yesterday’s part 1 post, I’d recommend clicking here and reading that first. Otherwise today’s peeves may lack context.

Jessica Mann’s Deadlier than the Male. If you haven’t had the chance to read yesterday’s part 1 post, I’d recommend clicking here and reading that first. Otherwise today’s peeves may lack context.

So Part 2 of Mann’s book starts with a fairly random introduction and attempts to justify the notion that whilst the work of first class authors such as Shakespeare, are not added to by knowing their life history, nor lessened if you do not, it apparently is the case for the work of second class writers and the Queens of Crime are unsurprisingly being lumped into the latter category. This point is then backed up by extensive description of the work and lives of Ian Fleming and John Buchan. It is the questionable point to make in the first place, yet the description-focus of the chapter derails any argument that was being initially built up. The introduction finishes on this note, in reference to the work produced by the Queens of Crime:

‘Obviously the events they narrated were not in in themselves desirable; there is no wish fulfilment in the action. But I believe that their experiences tended to induce in them similar assumptions: that stability was desirable, and when threatened, should be restored; that reason should prevail over violence…’

Given how critical Mann is of GAD novels lacking ‘wish fulfilment,’ the first part of this statement seems a trifle self-contradicting, as one of her bizarre thesis points is that the wish fulfilment involved in the Queens of Crime’s work is part of the reason their work is so popular. Equally the second half of this statement is so generic that it applies to a lot of vintage crime writers, male and female, so can hardly be attributed as a feature of success to five women only.

Chapter 5: Agatha Christie

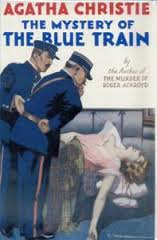

The biographical details in this chapter, in keeping with the ones that follow, are ones fans will be fairly familiar with, though I imagine Mann’s opinions will probably have most of your attention. First up when discussing how Christie’s low mood is not perceivable in The Mystery on the Blue Train, we have this rather unnecessary  derogatory explanation:

derogatory explanation:

‘But she used her formula with unfailing efficiency, presenting puzzles and solutions in a form as lacking in emotion as a comic strip. Her participants are not characters, but collections of characteristics, which require no involvement on the writer’s part, and offer the reader an escape without any involvement on his. The Mystery on the Blue Train exposes no more of the depression Agatha Christie felt when she writing it than a series of algebraic equations would.’

This excerpt is a good example of how Mann over-elaborates a basic point with personal opinions; with the inevitable effect being one of undermining.

I’ve not read any of Christie’s Mary Westmacott novels so I’ll have to let those of you who have, decide whether this remark is accurate:

‘They are not good novels, being as unadorned, and occasionally as ungrammatical in style, as the detective stories, and almost as simplistic about human behaviour…’

Nevertheless the thought does grow on you as you read this book that Mann doesn’t seem to like or value the books of the authors she is writing about. Or if she does then she is hiding it very well… Also at a loss to see how such passages of the book are meant to aid Mann’s argument.

Another weakness which occurs a number of times is Mann’s over-confidence in making certain statements, using the dubious word ‘always,’ for points which easily have exceptions: ‘In Christie’s fantasy land, the innocent were always compensated.’

Perhaps this next error is more forgivable as Mann did not have access to Christie’s notebooks and papers, as John Curran’s work  definitely proves the last part of this statement to be false:

definitely proves the last part of this statement to be false:

‘She had written that there are few things more desirable than to be an accepter and an enjoyer. Agatha was able to enjoy almost anything. This quality, so enviable and fortunate for its possessor and her family, was probably the reason for the failings which scrutineers of her work detect. A person who accepts is unlikely to question.’

However, you could argue that somebody having to work with more limited resources should probably be more careful in the statements that they make. Like yesterday, I have a book I would recommend in replacement of this one and today I would suggest reading From Agatha Christie to Ruth Rendell (2001) by Susan Rowland, as a better book.

Chapter 6: Dorothy L. Sayers

Despite loving the college setting of Gaudy Night, Mann doesn’t really have anything complimentary to say about Dorothy L. Sayers, either as a person or for her work. Mann shifts the focus from the texts and delves into psychology, a field switch I don’t think worked particularly well. Mann makes a big show of dissecting her  personality, but her points are thoroughly undermined by personal bias and criticism, along with a lack of substantial evidence. It’s a chapter which has an unpleasant undertone and it does feel like Mann had a bit of a narrative agenda with it, especially since poor behaviour shown towards Sayers by others is consistently defended, whilst Sayers’ perceived faults are not given the same curtsey. Overly strong assertions abound in this chapter.

personality, but her points are thoroughly undermined by personal bias and criticism, along with a lack of substantial evidence. It’s a chapter which has an unpleasant undertone and it does feel like Mann had a bit of a narrative agenda with it, especially since poor behaviour shown towards Sayers by others is consistently defended, whilst Sayers’ perceived faults are not given the same curtsey. Overly strong assertions abound in this chapter.

As to Sayers’ work, her characterisation is viewed poorly and Mann is keen to emphasise how in this respect Sayers was ‘more of a reporter’ of people she already knew, ‘than an inventor’ of characters. Yet I think Mann overreaches herself when she attempts to explain why Sayers firstly gave up writing ‘a second-class type of imaginative work,’ before secondly suggesting why she decided to write it in the first place. So beginning with the former:

‘I suggest, with no other evidence than intuition, that the real reason Dorothy gave up writing fiction was that she had used up all her experience, described all the places she knew well, presented all the characters, said all she had to say on subjects other than religion.’

Whilst it is nice to see Mann being a little more tentative, I question whether ‘intuition,’ of this kind, has a place in such work and equally it would be helpful if Mann had explained where this ‘intuition’ came from.

As to why Sayers supposedly wrote detective novels in the first place, Mann offers us this theory:

‘An education in literature is a danger for any potential novelist; their own fiction always seems so inadequate in comparison with what they have read and studied. In this, I believe, lies another reason for Dorothy’s initial choice to write ‘genre’ fiction – her unwillingness to complete a straight novel. She did not want to be compared with unattainable models.’

Mann admits she had no access to private papers and therefore relies on second-hand evidence from those who have. Consequently statements like this one above lack weight and seem more influenced by Mann’s own low estimation of genre fiction.

Chapter 7: Margery Allingham

Whilst we’re on Allingham I am looking forward to getting stuck into the new biography written about her, which is called The Adventures of Margery Allingham (2019) by Julia Jones. I’m hoping it will answer some of the questions I have about this author, as Mann is somewhat elliptical on certain parts of her life. I found this reticence unusual, given how readily she dished the dirt on Sayers. Any fault finding in this chapter is much more softly done. Mann shares far fewer psychological insights so this chapter was far more readable than the previous. Although, perhaps as a consequence her thesis point is somewhat noticeable by its absence, as the chapter does little more than inform the reader of Allingham’s life and include a through brief quotes from the books.

Chapter 8: Josephine Tey

In comparison to previous chapters which are 20-40 pages long, this one is a mere 7 pages. Tey was quite a private person so Mann may well have had less biographical information to play with, yet to not  then use the chapter to provide a more in depth analysis of the texts and really explore the argument Mann is trying to make, seems curious. Readers interested in discovering more about Tey may wish to try Jennifer Morag Henderson’s Josephine Tey: A Life (2015). However, I did learn something new about Tey, which was that the murder method used in Miss Pym Disposes, may have been influenced by an accident Tey had whilst teaching.

then use the chapter to provide a more in depth analysis of the texts and really explore the argument Mann is trying to make, seems curious. Readers interested in discovering more about Tey may wish to try Jennifer Morag Henderson’s Josephine Tey: A Life (2015). However, I did learn something new about Tey, which was that the murder method used in Miss Pym Disposes, may have been influenced by an accident Tey had whilst teaching.

Chapter 9: Ngaio Marsh

In keeping with the last couple of chapters, personal criticisms are once more toned down, though the odd back handed compliment does crop up from time to time. Even at this stage I was boggled as to why Mann so consistently drew attention to the faults she perceived in their work, when she was, in theory, supposed to be looking at why these writers were so successful.

Sweeping remarks equally find their way into the text, such as Marsh’s novels ‘avoid[ing] social judgements.’ Such a statement doesn’t take her later novels into account, nor does it help Mann’s case when, sentences later, she contradicts herself by commenting on role of race in some of Marsh’s novels.

Damning comments then centre on Marsh’s characterisation due to Marsh not putting much of herself into her characters. To be honest none of these writers can do characterisation well if we believe Mann, regardless of what they do: include more of self/less self or greater/lesser depth of character. Each combo is criticised one way or another. This is encapsulated in the following passage:

‘So we are all left with a corpus of work which is pleasant and entertaining but not entirely satisfying. One feels that Allingham put all she could into her work, that Sayers put in far more than she intended, that Christie used as much as was appropriate for characters who were not intended to inspire more interest than a puzzle-plot required. But in Marsh’s work one sense withdrawal.’

Glimmers of truth may be found, but the certainty of tone overwhelms them and I am not convinced that such subjective issues should be the foundation for an argument, as I imagine for every reader who doesn’t enjoy Marsh’s work or thinks there is a ‘sense of withdrawal,’ there will be another reader who thinks the exact opposite. None of this answers the question Mann posed at the start of her book, which I guess left me feeling frustrated.

With the benefit of hindsight I also have to admit to a brief smile when I read this closing statement:

‘… the author’s reticence has diminished the life of her novels. It is this, more than anything, which may determined whether they survive.’

When reading such sentences it is is easy to forget that the subject of Mann’s thesis is this writer’s success. I’m not sure whether Mann has, metaphorically speaking, any feet left given how much she’s shot them.

Chapter 10: Conclusion

Huzzah we made it to the end! Now you might be expecting Mann to finally get to grips with her thesis and succinctly outline why these Queens of Crime are so popular. Well think again…

First up we have this:

‘Crime novelists, on the other hand, as we have seen, are particularly reticent about their own personal lives. They wish to write about things which are outside of themselves, and recoil from exposing their own personalities to public view.’

This might very well be true, yet it seems a bizarre statement to make given Mann’s chapter on Sayers and the fact that a key tenant of her thesis was that these writers put themselves into their novels to greater or lesser degrees. However, a u turn at this stage in the book was beyond surprising me, given what had come before.

The majority of the conclusion considers the then modern detective novel, which you will not be shocked to hear, is something Mann much more approves of and she spends much page space elevating contemporary works and kicking classic novels into the ditch:

‘In the classic detective story one remembers the settings and a few of the characters; one reads them with pleasure. The modern detective story can be equally memorable, often more so; but it lifts the mask of polite society, the veil of incomprehension, to reveal something from which one might prefer to avert one’s eyes. Such books are remembered with respect for their understanding and revelation; but they rarely offer the innocent pleasure which less ambitious novels gave.’

…. Oh boy! Reading that passage is like someone telling you a piece of grass is pink. The extent of the wrongness almost seems incomprehensible, though I do have to keep reminding myself it is my own perception of wrongness, as no doubt Mann’s opinion is one others may share. Though for someone who enjoyed Gaudy Night, it seems peculiar that she would categorise it as something which is ‘less ambitious.’ A brief defence of the vintage crime novel then follows, but Mann hardly makes a winning case.

And just before the book closes we get a surprise pot shot at Christianna Brand whose:

‘… characters are amusing and attractive; her heroines naïve and sweet. The writers who began their careers in the last twenty years have colder eyes.’

I have run out of ways now to express befuddlement at statements which seem to so rapidly be disqualified by the very texts the writers wrote.

After that bombshell I don’t think anyone will be surprised by my final rating of Mann’s book. I do wonder whether, like my review of Edwin Green’s French Farce, this book may seem so bad that others will want to read it and experience it for themselves. All I can say is you have been warned and that if you want to read more about the genre or these authors there are far stronger works to consider first. But more on that anon…

Rating: 1.5/5

“[W]hilst the work of first class authors such as Shakespeare, are not added to by knowing their life history, nor lessened if you do not, it apparently is the case for the work of second class writers and the Queens of Crime are unsurprisingly being lumped into the latter category.” How is it she determines which writer falls into which category? And the implication that the writing of a “first class writer” is in no way affected by their life experience, yet that of “second class writers” is, just seems absurd.

Coincidentally, in 2012 Mann addressed the “limited resources” issue (http://bookoxygen.com/?p=5758). In short her opinions at the time were formed based on what she felt was lack of information available to her about these writers, and her knowledge of them reflects “what these authors would have wanted the public to know”.

And most of all…thank you for such an in-depth review of, what sounds like a very painful read for you 🤣!

LikeLiked by 1 person

‘what these authors would have wanted the public to know’ – yeah I’m sure Sayers would have loved her chapter!

Hoping my October reading is going to pick up now.

LikeLiked by 1 person

…So you didn’t like it then? 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

What gave me away?

LikeLike

Yet another “critical work” that reveals the author’s own shallow reading in the genre and a dearth of knowledge about what actually was written and published during the Golden Age — and for some decades after, too. Too often it appears that her examples were cherry picked in order to support her flimsy and wholly contradictory thesis. As all of our examinations of hundreds of books on these various mystery blogs have shown there are dozens of writers who created fully fleshed and complex characters, tackled taboo and fascinating topics with ingenuity, compassion and intelligence, and wrote books that will stay with us for life. I just can’t get over all these dismissals of the past and the never-ending celebration and self-congratulatory opinions about the present. It’s so boring to read modern writers patting themselves on the back and claiming to have surpassed the writers who invented a genre that they make their living off of. And so few of them have any right to claim that their work has invigorated the new and improved crime novel they so want to extol. Thanks for this trenchant analysis.

LikeLiked by 3 people

You’re welcome! Took one for the team I think with this one! Blogs have definitely increased my awareness of the variety of authors and texts going under the vintage crime umbrella and they provide an excellent caution against making large generalisations about the genre based on one or even two authors, (something some academic titles have fallen foul of).

LikeLike

Truman Capote was rather proud that in In Cold Blood he was “more of a reporter” and less “an inventor.”

The book seems to have been written with the idea, “setting aside the mystery part, there’s not much that makes these books interesting.” It’s a bit like saying, setting aside the poetry bit, King Lear is kind of a dumb story.

Thanks for taking two for the team.

LikeLike

You’re welcome! Similarly, I read Crime Fiction: A Very Short Introduction a few years back and their choice of writer was bizarre to say the least, as aside from committing gross errors, (such as placing Miss Marple in the novel of The Murder of Roger Ackroyd,) the writer clearly didn’t enjoy crime fiction, vintage or otherwise. I think they may have cared for some US writers but Britain needn’t have wasted the paper their work was printed on, if this author was to believed.

LikeLike

Another example of opinion being treated as though it were fact.

LikeLike

[…] non-fiction book, which I have reviewed in two parts which you can find by clicking here and here. A consistent weakness of this book was the fact it undermined its’ own argument and never […]

LikeLike