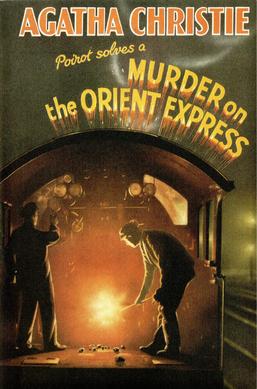

My final post on excursion and travel mysteries for the Tuesday Night Bloggers is another re-read from my first TNB post of the month listing my favourite holiday and transport themed detective novels. I read Murder on the Orient Express (1934) quite early on in my reading of crime fiction and unfortunately I did go into it knowing the solution, as I can imagine to an uninfluenced mind it would be even more impressive. Despite this though it is still a novel I love. I was intrigued by what my re-reading experience would be like. What would I get from it? Would I even still like it? For those who are not familiar with the plot I would probably advise reading the book before reading this post, as the style of this review is a little different from my normal reviews. What follows are 11 ideas which interested me about the story and therefore there will be spoilers.

Interesting Idea No. 1 – Poirot in the Spotlight

One of the things I enjoyed from the re-read was looking at how the other characters perceive Poirot and it is fair to say that they definitely tend to underestimate him and treat him as an outsider. For example, Mary Debenham’s first impression of him is: ‘What an egg-shaped head he had!… A ridiculous-looking little man. The sort of little man one could never take seriously.’ Interestingly the adjective ‘little’ is repeatedly used to refer to Poirot throughout the text, which emphasises the idea that the suspects do not realise Poirot’s true capabilities and value, as ‘little’ has a rather devaluing effect. Colonel Arbuthnot in particular regards Poirot as “other” or “foreign,” though arguably in the text this idea is revealed through Poirot’s perception of Arbuthnot and not through Arbuthnot’s speech. For instance it is said that Arbuthnot’s ‘eyes rested for a moment on Hercule Poirot, but they passed on indifferently. Poirot, reading the English mind correctly, knew that he had said to himself, ‘Only some damned foreigner.’’ Another example is during Poirot’s questioning of him where Arbuthnot’s response is described in the following way: ‘“And that,” his manner seemed to say, “is one for you, you interfering little jackanapes,”’ with poor Poirot being the ‘jackanapes’ in question. MacQueen’s response to Poirot can also be seen to have a belittling effect as when he hears Poirot’s name he says that ‘it does seem kind of familiar – only I always thought it was a woman’s dressmaker.’ Even those who are helping to assist his investigation aren’t sure what to make of him as Doctor Constantine thinks to himself that Poirot ‘is queer, this little man. A genius? Or a crank?’ The closest Poirot gets to a compliment is from Mr Hardman who says he is ‘a slick guesser.’

Although it could be said that because Poirot is regarded as an outsider and categorised merely as a “foreigner,” he is then able to spot those who pretend to be “foreign”. For example Countess Andrenyi is said to have ‘a very foreign appearance which she exaggerates’ and in fact it turns out that she is an American who is pretending to be otherwise.

Another aspect of Poirot’s character I noticed in this book is that he undergoes to an extent apotheosis (the act of being glorified and divined), as within this story Poirot does take on an almost super human or god-like status. For example the tale opens with Poirot closing a case, a case which lead to ‘a very distinguished officer… commit[ing] suicide.’ Therefore Poirot’s successful concluding of case can also entail death. But he also has the power to give people back their lives, literally and in terms of happiness as alongside the suicide his detecting powers change ‘anxious faces’ into happy ones and the client tells Poirot that he ‘averted much blood shed.’ Additionally, Poirot’s role as a detective is given a more dangerous and predatory slant when he is said to be ‘like a cat pouncing on a mouse,’ an feline image which also crops up in the Miss Marple stories and in both instances it suggests that it is the detective in the novel who has the most power. Poirot’s god-like status is really emphasised at the end of the novel when he allows a false version of events to be given to the authorities. Other phrases which reinforce this image of Poirot are when he says ‘I belong to the world…,’ which conjurors up the idea of Poirot being some sort of global resource and when M. Bouc says to Poirot, ‘If you solve this case… I shall indeed believe in miracles.’ Of course Poirot does solve the case which leads to the idea that this success is akin to producing feats which are beyond usual human powers.

Interesting Idea No. 2 – It’s all in the eyes

Something I noticed in particular during this re-reading was the attention given to characters’ eyes and the details Christie uses to describe them. Shakespeare is famous for writing in one of his sonnets that ‘the eyes are the window of the soul’ and in this novel I think a lot of information can be gleaned about characters based on their eyes. For example, Mary Debenham’s eyes are depicted as ‘cool, impersonal and grey,’ which to an extent reflects her character or at least how she wishes to be seen. Although, under the pressure of the investigation this emotionlessness crumbles. Ratchett’s eyes also expose his true nature, as although on the face of it he looks respectable, Poirot quickly sees that his ‘eyes belied th[is] assumption. They were small, deep set and crafty.’ They are also described as ‘small cruel eyes’ and he is said to give ‘a strange malevolence, an unnatural tensity in the glance’ when looking at Poirot. What we deduce about Ratchett at this point foregrounds the information we find out about him later.

And what about Poirot’s eyes? Christie says when examining Ratchett’s compartment after the murder, Poirot’s eyes ‘were darting about the compartment. They were bright and sharp like a bird’s. One felt that nothing could escape their scrutiny.’ This description of Poirot’s eyes reminded me of Gladys Mitchell’s Mrs Bradley whose eyes are presented in a similar way. For example in The Mystery of a Butcher’s Shop (1929) she is said to fix ‘the vicar with an eagle eye’ and her eyes are said to be ‘beady’ and ‘bird-like,’ as well as ‘sharp.’ Descriptions of her eyes in The Saltmarsh Murders (1932) even go as far as suggesting that she fixes people ‘with the most frightfully basilisk eye,’ which implies she is deadly, as the basilisk’s stare is meant to kill. Poirot is not portrayed as deadly in his description, but there is still a sense that he will discover the truth which the suspects vainly try to hide. Another parallel between them is that their eyes reflect when they have discovered something important. In the case of Poirot you know he is on to something when his eyes ‘twinkle,’ whilst for Mrs Bradley in The Mystery of a Butcher’s Shop and Death at the Opera (1934), her eyes are said to be ‘bright.’ Additionally, Poirot’s eyes are also likened to a ‘cat’s,’ which links into the theme I discussed earlier of cats being used to imply a more predatory or hunter’s side to the detective’s role.

The way the suspects’ eyes are described also changes as the novel progresses because as the investigation picks up speed and the suspects get more anxious their eyes start to represent their internal desire to find out how much Poirot really knows. For example Countess Andrenyi eyes’ are said to ‘watch… [Poirot] curiously,’ whilst when Poirot mentions how the Armstrong case is involved, Mr Hardman is said to ‘cock… an inquiring eye.’ The strongest example though can be seen in the suspect, Antonio Foscarelli. He is very loquacious when he is first interviewed, but during his second questioning this rapidly changes: ‘The big Italian had a wary look in his eye as he came in. He shot nervous glances from side to side like a trapped animal.’ This last phrase ‘trapped animal’ intrigued me as the only other character to be referred to as an animal in a general sense is the loathsome victim Mr Ratchett. Perhaps in a way though, by taking part in the revenge against Ratchett, Foscarelli has become more like Ratchett in that they have now both taken a life, as committing murder is understandably an experience which affects you.

Interesting Idea No. 3 – The Victim

For the majority of the novel we are only able to form impressions of Ratchett through what other people say of him. There is little opportunity to make such impressions directly from his actions and speech. But I think the image which struck me the most about Ratchett is given by Poirot early on in the story after looking at him:

‘I had a curious impression. It was as though a wild animal – an animal savage, but savage! … had passed me by…The body – the cage – is everything of the most respectable – but through the bars, the wild animal looks out… I could not rid myself of the impression that evil had passed me by very close.’

Even before Poirot knows of Ratchett’s past he senses there is something wrong with him and I think the image of a respectable exterior hiding a savage and violent nature is a key concept which can be found in many Golden Age detective novels.

Interesting Idea No. 4 – The Crime Setup

Something I have always liked about this book is its setup: a group of people on a train which is trapped in snow. As not only does it allow for a closed set of suspects but it also provides a legitimate excuse for that group of people to be made up ‘of all classes, of all nationalities, of all ages.’ And the solution of the case is foreshadowed early on by Poirot when he imagines that all the passengers are ‘linked together by death.’ I also liked how because the train is trapped in snow and there are no convenient things like a mobile signal or an internet connection (mainly because to be fair they weren’t invented yet), Poirot can’t use ‘the facilities [usually] afforded to the police.’ He ‘cannot investigate the bona fides of any of these people.’ This of course affects the nature of Poirot’s investigation, but I think in a good way as he verbally has to be much more astute and clever in order to ascertain whether people are lying or not.

Interesting Idea No. 5 – Mary Debenham

For me Mary Debenham was a particularly interesting character as normally characters like hers are innocent suspects, who tend to be down to earth, intelligent with a hint of wry humour and assist the sleuth and/ or have a romantic subplot. This is epitomised in her response to Colonel Arbuthnot’s comment on being a governess: ‘I don’t like the idea of your being a governess – at the beck and call of tyrannical mothers and their tiresome brats.’ She refutes this stance by replying that ‘the down trodden governess is quite an exploded myth. I can assure you that it’s the parents who are afraid of being bullied by me.’ Instead though in this story she is a killer, which is evidence of Christie playing around with character types. Knowing this from the very beginning made me look again at how Debenham acts during the book and in terms of suspicious behaviour she is the most useful to watch, as Poirot and therefore us have the most time to observe her and how her behaviour alters. For example when she thought she was going to miss the Orient Express train she was practically distraught, yet when the Orient Express become snow bound she is much philosophical about it: ‘Her voice sounded impatient, but Poirot noted that there were no signs of that almost feverish anxiety which she had displayed during the check to the Taurus Express.’ Furthermore, her intelligence also shows when she is being questioned by Poirot as she often pre-empts and predicts what Poirot is going to say or do and she can tell what he is thinking sometimes. It is not surprising that Poirot says to her, ‘You are a strong character… You are, I think, the strongest character amongst us.’

Interesting Idea No. 6 – Sleuthing Prejudices

Poirot is not the only one with an opinion about this case as other passengers and train workers also have ideas about who the killer might be and it is in these suggestions that people reveal their own prejudices. For example the Chef de train suggests the killer was a woman due to the numerous and inconsistent stab wounds: ‘“Women are like that. When they are enraged they have great strength.”’ Whilst M. Bouc has a bee in his bonnet about Foscarelli, as he is convinced that because the victim was an American criminal, the killer must have been a ‘gangster or a gunman.’ Foscarelli fits the bill in M. Bouc’s eyes as he ‘is a large American… a common-looking man with terrible clothes. He chews the gum which I believe is not done in good circles.’ M. Bouc’s prejudice against Italians becomes even more overt later on in the novel when he says of Foscarelli that ‘he has been a long time in America… and he is Italian, and Italians use the knife! And they are great liars! I do not like Italians.’

Interesting Idea No. 7 – Suspect Prejudices

However, it is not just the wannabe sleuths that have prejudices. Our group of suspects also host a number of prejudices, especially against “foreigners”. For example it is said that the Ratchett’s valet, Masterman had ‘a low opinion of Americans and no opinion at all of any other nationality.’ Moreover, even when he is trying to vouch for someone, his prejudices against non-British people are exposed: ‘Tonio may be a foreigner sir, but he’s a very gentle creature – not like those nasty murdering Italians one reads about.’ Mrs Hubbard is another character with similar views such as when she unfairly says when they get stuck in the snow that ‘there isn’t anybody knows a thing on this train. And nobody’s trying to do anything. Just a pack of useless foreigners.’ Moreover, she is shown to have a superior view of Western culture and she asserts that people should ‘apply… Western ideals and teach the East to recognise them.’

Although, it can be argued that the American and British characters are also stereotyped or satirised, with characters such as Foscarelli describing the English, Masterman as ‘the miserable John Bull… [with the] very long face’ and goes on to sum up England as ‘a miserable race.’ However, I think there is another reason why the characters might be expressing such prejudices so overtly which is that they do not want Poirot to consider the idea that they all have a common cause which unites them together. They want to be seen as disparate people and it could be said that Christie also does not want her readers spotting any comradery between all the characters. Moreover, spouting certain cultural stereotypes also helps some of the suspects to build up a false persona. Additionally some of the characters rely on stereotypes more than others. This affects which characters readers will like and be drawn to. Again this makes it harder to consider that characters you like and characters you dislike are working together.

Interesting Idea No. 8 – ‘A Theatrical Kind of Crime’

Early on Poirot realises the artificiality of the crime scene. He says that ‘one cannot complain of having no clues in this case. There are clues here in abundance… This compartment is full of clues, but can I be sure that those clues are really what they seem to be?’ In fact Poirot thinks some of these clues are too convenient such as the initialled handkerchief saying it is ‘exactly as it happens in the books and on the films.’ He also refers to the crime as having ‘design’ and as a ‘planned jigsaw puzzle.’ A while ago I reviewed Lisa Hopkin’s book Shakespearean Allusion in Crime Fiction (2016) and one of her arguments was that some detective writers use allusions to Shakespeare to emphasise the sense of artificiality in the crime or crime scene. When discussing whether there were two separate murderers, Poirot says that ‘we have here a hypothesis of the First and Second Murderer as the great Shakespeare would put it.’ Yet this allusion is not there to vindicate the theory, but to undermine, which is followed up by Poirot’s own comment that the idea ‘sounded to me a little like the nonsense.’ Artificiality then is something to be wary of in this book as the conspirators deliberately make the crime scene ridiculous and full of clues in order to conceal themselves, as they hope within such an array of clues, no detective can find the truth. Another instance when the crime scene’s artificiality is noted is when Poirot and company consider how the killer left Ratchett’s compartment (there being one open window and two seemingly impossible door exits). Doctor Constantine is befuddled by it, but Poirot replies by saying that this ‘is what the audience says when a person bound hand and foot is shut into a cabinet – and disappears.’ Yet Poirot is not taken in by the ‘trick’ and the idea of the crime being like an illusion is also voiced when M. Bouc says ‘show me how the impossible can be possible.’ Though interestingly despite saying he will solve how the ‘trick’ was done, Poirot does not identify himself as ‘a magician.’

Interesting Idea No. 9 – A Matter of Class

Class and rank are two important issues in this story as firstly they affect how people treat others. M. Bouc for example admits that he is a bit of a ‘snob’ and this is reflected in how he wants to interview the suspects. Additionally class is used as a means for deciding who the handkerchief (found in Ratchett’s room) belongs to. Although Princess Dragomiroff’s maid, Hildegarde has the correct initials for the handkerchief, its material and style is deemed to be out of her class. Class is also a reason for lying as Princess Dragomiroff says she lied for Countess Andrenyi because she believes ‘in loyalty – to one’s friends and one family and one’s caste.’ Although the class system is not always taken entirely seriously. For example Doctor Constantine asks Poirot to explain what Arbuthnot meant by calling Debenham ‘pukka sahib.’ Poirot replies that ‘it means that Miss Debenham’s fathers and brothers were at the same kind of school as Colonel Arbuthnot.’ Constantine is rather disappointed by this explanation saying ‘Oh! Then it has nothing to do with the crime at all.’ And arguably from this we can see the implication that class and family background cannot be used as a way of detecting who the criminal is and the solution bears this out.

Interesting Idea No. 10 – Comic Touches

Something I think which has not always been necessarily picked up on in adaptations of this novel are the many comic moments it has and I think it is these moments which make the ending more stark as you’re not expecting things to turn out that way. Humour in this book is sometimes conveyed through character descriptions such as Miss Ohlsson’s: ‘she’s like a sheep, you know. She gets anxious and bleats.’ Another moment is when Mrs Hubbard faints on finding the murder weapon covered in blood in her sponge bag: ‘With more vigour than chivalry, M. Bouc deposited the fainting lady with her head on the table’ and Doctor Constantine is less than interested in her distress as ‘his interest lay wholly in the crime – swooning middle aged ladies did not interest him at all.’ A final example is when Poirot tells M. Bouc and Constantine to sit quietly and cognate over the case, as they spectacularly fail at this, with their trains of thought (which we can view) degenerating from thinking about the crime into more personal matters.

Interesting Idea No. 11 – Justice

Justice is an important component in this novel because right and wrong are not clear cut. There is moral ambiguity. Yet I don’t think Christie overplays her portrayal of complicated justice. Nor is it over explained. Poirot takes the law into his own hands, offering a false solution in order to prevent lives being further blighted. Such blighting Poirot deems as pointless, despite not agreeing with what they did. The text is quite sparse in describing Poirot’s dilemma and adaptations of this novel have fleshed it out. Moreover, the story is very blunt in its ending as there is not lots of discussion over what to do. The narrative simply cuts to M. Bouc and Doctor Constantine’s (who can be seen as representative of the book’s readers perhaps) final judgement. No imagery. No evocative metaphors. Just a definitive final decision. And in some ways I think it works better that way as it makes the ending more shocking and causes the reader to go back and think about the book. One of the mysteries of this story will always be ‘why did Poirot go against the law this time?’ Granted the victim was a horrible and horrendous person, but one feels that Poirot surely has encountered such victims before. What made him go against his normal principles this time? Was it the sheer number of lives which would be affected?

Overall Thoughts

At the beginning of this post I wondered whether I would still like this novel after re-reading it. Thankfully this is an easier question than the one I posed in the previous section. The answer is definitively yes. I love the atmosphere and world Christie creates. I love Poirot’s investigation, now spotting more of the subtleties and verbal clues that I missed on first reading it. I found new layers to many of the characters. They are more than character types. My final thought brings us back to the beginning of the novel and the concept of novel continuations. There is part of me that wants to know more about the case Poirot completes at the start of the book, as Christie certainly makes it sound intriguing. Maybe someone will write a continuation novel which explores this unwritten case, perhaps also shedding some light on Poirot’s state of mind before boarding the Orient Express.

Rating: 4.5/5

SPOILER! SPOILER! I’ve read somewhere that Christie wrote this one in response to a friend’s request for a mystery in which ‘they all did it!’ I’ve always admired the way she took that plot device/trick and, by incorporating some of the details from a real life event (the Lindbergh baby kidnapping), actually managed to make the concept work, even if it’s not quite believable. It’s probably why this book has stood the test of time, whereas others in her canon have not.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes Christie did pull off a number of classic plot devices such as this one, and its opposite in And Then There Were None, as well as in The Murder of Roger Ackroyd.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ooooh, you’re stirring up controversy here, Kate, and it compels me to respond to a few of your points. If I’m not exactly accurate here, it’s because I haven’t re-read this one in a couple of years. (SPOILERS, SPOILERS):

I always read the inclusion of class and racial prejudices here as deliberate on the part of the murderers AND as a clue to the truth. In AMERICA, there are no class divisions! In AMERICA, we are all equal and can join together, servant and master, in this epic scheme to bring down a villain. (It’s all hooey – there is plenty of prejudice here, but . . . ) It’s important, for example, that Masterman seem snooty so that his providing an alibi for Foscarelli seem almost reluctant rather than part of a plan. As for the way they treat Poirot, well, his whole career is marked by people underestimating him because he looks like a dressmaker or hairstylist! The very artificiality of the crime scene makes it look like they figured the cops would be too stupid to see through their plan.But I wonder how many of their strategies they would have exercised without having a man of Poirot’s intelligence around to misinterpret them. The crying out in French by “Ratchett” after pointing out to Poirot that he spoke no languages, the business with the knife in Mrs. Hubbard’s bag, the lady in the scarlet kimono . . . The crime is purposely made more complex, which in itself is a clue because what pair of Turkish criminals would act this way. Are we supposed to believe that they traipsed through the train, gathering a pipe cleaner, a handkerchief, a button from a conductor’s uniform, etc. to falsely incriminate passengers? Why do that, when a simple stabbing and an open window would have pointed more easily to strangers? It’s one of the reasons people complain that this is an unbelievable plot, but it also points to a certain desire of the killers to provide a signature to their crime.

I think there is a lot of humor in the Albert Finney version of the story. Most of the laughs in the book come from Mrs. Hubbard (Linda Arden says, “I’ve always fancied playing comedy parts.”), and Lauren Bacall, not a comedy actress, gets some laughs in, but I think Sir John Gielgud as the valet is very amusing, Anthony Perkins as MacQueen does a riff on his Norman Bates from Psycho, and Ingrid Bergman all but steals the show as Greta Olsson, making the nurse’s pathos quite funny and winning an Oscar for her efforts. David Suchet killed the humor because he wanted the whole thing to be about Poirot’s Catholic guilt over letting someone get away with murder. I found that fascinating when I first saw it, but you’re quite right that the ending of the novel is swift and merciless.

Martin Edwards wrote in his study of the Detection Club how many of its members let killers get away with murder as the concept of justice was more fluid in a lot of GAD fiction. The killers in Orient Express have constructed a plot that screams, “We are a jury!” which compels the trio of investigators to allow them to “leave the jury room.” I find it much more interesting to discuss why Poirot let Dr. Sheppard kill himself rather than face the courts. Is it the fact that they became friends? Is it pity for Caroline Sheppard? Why does Poirot show this when the killer is completely remorseless, having driven one person to suicide, cold-bloodedly murdered his best friend, and framed a perfectly lovely young man for the crime? Now THAT would make for an interesting conversation for sure!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Heck I didn’t realise I was causing controversy! Though from what you have written it seems like you are thinking along similar lines to me, (unless I have misunderstood you). I have only seen the Suchet and not the Finney version, so it is interesting to see the earlier version had more humour in it.

I suppose the difference between letting the 12 killers go free and allowing Acroyd to commit suicide is that Acroyd is still receiving the punishment of death, just not via a noose, whereas in the other case the others are avoiding their legal punishment and get to live although they will have to live with the guilt. Perhaps for Poirot as long as the truth is known e.g. Acroyd was the killer and that no one else will take the blame, whether Acroyd’s death is by his own hand or the by law may not matter so much. In the other instance the truth is concealed which is what makes the difference for me.

LikeLike

What Brad said, pretty much.

Also, this makes me want to write a “killers escaping justice” post about Christie, because there’s at least one more instance of this that some themes could probably be drawn from. But, y’know, as you’re both more likely to do a far superior job of it than I would, I’d almost prefer one of you wrote it… 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s a book that I have re-read much less than some others by her, but your piece makes me think I must get it out and consider all these matters.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I surprised myself with the amount of stuff I got from re-reading it.

LikeLike

[…] on the Orient Express has been reviewed at Bitter Tea and Mystery, Cross examining crime, Mysteries in Paradise, Past Offences and Reactions to Reading among […]

LikeLike

[…] I don’t think it has the same celebrity status as some of Christie’s other titles such as Murder on the Orient Express (1934) or And Then There Were None (1939). Then again this may be due to the fact it hasn’t been […]

LikeLike

[…] 2. Samuel Ratchett in Murder on the Orient Express (1934) […]

LikeLike

[…] made the right choices. I decided to veer away from the ones which have been heavily adapted such as Murder on the Orient Express (1934) and Death on the Nile (1937), as I think their plots were a little too well-known, even by […]

LikeLike

[…] (a Tommy and Tuppence case from Partners in Crime (1929)), At Bertram’s Hotel (1965) and in The Murder On the Orient Express (1934), a woman enveloped in a scarlet kimono becomes a red herring for Hercule Poirot – not that […]

LikeLike

[…] referencing of history also comes from more modern times with references to real life crimes (see Murder on the Orient Express (1934)) and both the world wars crop up from time to time. In The Mysterious Affair at Styles […]

LikeLike

[…] of people on a train, whose journey is prevented by the weather, giving the story a slight nod to Murder on the Orient Express (1934) and the way the solution is pretty much handed to the police at the end when they arrive, […]

LikeLike

[…] in Manning Coles’ A Drink to Yesterday (1940) and Nicholas Blake’s The Beast Must Die (1938). Murder on the Orient Express (1934) is probably one of the most famous examples of a revenge based murder mystery, highlighting […]

LikeLike

[…] Act Tragedy, writing that ‘we believe in the reality of the people.’ Although in her review of Murder on the Orient Express, which avoids any discussion of its major novelty, she quibbles over Poirot’s deductions […]

LikeLike

[…] on trains was already a well-established trope in mystery fiction by this point, from Christie’s Murder on the Orient Express (1934) and The Mystery of the Blue Train (1928), to Josephine Tey’s The Singing Sands (1952), […]

LikeLike

[…] at one point is stuck in the middle of the desert, it is hard to not think of Agatha Christie’s Murder on the Orient Express (1934). I know Christie’s novel was influenced by the real life kidnapping of Charles […]

LikeLike

[…] is fairly luke warm, with the verdict being that it is a ‘standard brand’ (7th March 1942). The Murder on the Orient Express (1935), another famous Christie novel is summarised as ‘sauce piquante of super-deduction […]

LikeLike

[…] 1950: 42). Hercule Poirot is similarly depicted with his eyes being likened to those of a cat in Murder on the Orient Express (1934) and during the investigation he is said to be ‘like a cat pouncing on a mouse’ (Christie, […]

LikeLike

[…] Furthermore, Christie’s response to her agent when MGM wanted to do a screen version of The Murder on the Orient Express (1934) with Miss Marple in, is also highly […]

LikeLike

[…] for the X-ray fashion of peeking into character’s minds.’ Additionally he seems to have liked The Murder on the Orient Express so much, that it very likely inspired his own train bound mystery, Vultures in the Sky. Fear not, […]

LikeLike

[…] Suchet’s original moustache for the earlier series was based on a description in Murder on the Orient Express. It’s design was changed later when Chorion and Arts and Entertainment Network took over the […]

LikeLike

[…] justice into one’s own hands is regularly deplored.’ For both of these points she brings up Murder on the Orient Express. I am not disagreeing with mentioning this title, but I think a more powerful reading could have […]

LikeLike

[…] Equally Christie also shows how motherhood generates a load more reasons to bump someone off, from Murder on the Orient Express (1934) to The Hollow (1946). Even the prevention or termination of motherhood leads to poignant and […]

LikeLike

[…] Todhunter into the position he finally takes. In keeping with other mysteries of the 1930s, such as The Murder on the Orient Express (1934), this is a story which considers the justifiable […]

LikeLike

[…] Christie. Moreover, Christie also often opened her novels, such as in Death on the Nile (1937) and Murder on the Orient Express (1934), with a series of vignettes which shift from character to character and their viewpoints, […]

LikeLike

[…] Crossexamining Crime […]

LikeLike

[…] at CrossExaminingCrime shares eleven things she finds interesting about the […]

LikeLike

[…] And what about the famous Murder on the Orient Express? […]

LikeLike

[…] the covers they have received over time and what better book for this topic than Christie’s Murder on the Orient Express (1934). There is a ridiculous amount of covers for this one, so I am just giving the edited […]

LikeLike

[…] this here. Interview heavy mysteries are not automatically poorer mysteries, as I enjoyed much more Murder on the Orient Express (1934). The difference there was that I felt the reader gained a larger amount of information from […]

LikeLike

[…] refuses to take her on as a client, an action I remember him doing three years prior to this case in Murder on the Orient Express (1934). In that story he refuses to take Samuel Ratchett on as a client and whilst I am not saying […]

LikeLike

[…] me. Furthermore, the cast as a whole are fairly depressing, and this made me think of Christie’s Murder on the Orient Express where we have characters with troubles, yet they don’t produce a depressing effect on the reader. […]

LikeLike